One thing Japan has plenty of these days is milk.

Schools across the nation closed are closed as a countermeasure against infection, and that means not only no classes, but no school lunches either. Having temporarily lost some of their biggest customers, dairy farmers are hurting, and since Japan is a culture that deeply respects its agricultural workers, there’s been a social movement encouraging people to buy more milk to help pick up the slack. That, in turn, has led to people looking for new ways to use that milk, which has brought back a millennium-old Japanese food called “so.”

So reached its peak popularity in the Heian period (794-1185), but its history goes all the way back to the Asuka era, which started in 538. Historical records say that it was popular with the nobility, and since its one and only ingredient is milk, making your own so is Japan’s latest home cooking trend.

We’re lucky enough to have someone on staff who’d eaten so before its recent revival: our Japanese-language reporter Ayaka Idate. No, Ayaka isn’t a time-travelling lady of the imperial court, but she does have a passionate interest in history, and a few yeas back she visited a museum in Japan where guests could sample so.

Ayaka recalls so as being brown in color, with a crisp, powdery texture and a flavor like a sweet, rich cheese. Ready to do her part to help out the dairy industry, get in touch with Japan’s culinary heritage, and also just eat some dessert, she went to the store and procured two cartons of milk.

Detailed directions for making so are yet to be found by historians, but the basics are outlined in the Engishiki, a 10th-century text compiling laws and customs of the land at that time, which simply says to boil milk while stirring it.

Step 1 (also last step): Boil milk while stirring it.

The Engishiki calls for using one to of milk, which converts to about 18 liters of milk in modern measurements in order to make one sho (1.8 liters) of so. With no other ingredients involved, though, you can actually make so with whatever amount of milk you like, provided you’re willing to run the risk of anyone who’s read the Engishiki and is also a total snob snickering at you for making a smaller batch than the Heian nobles would have.

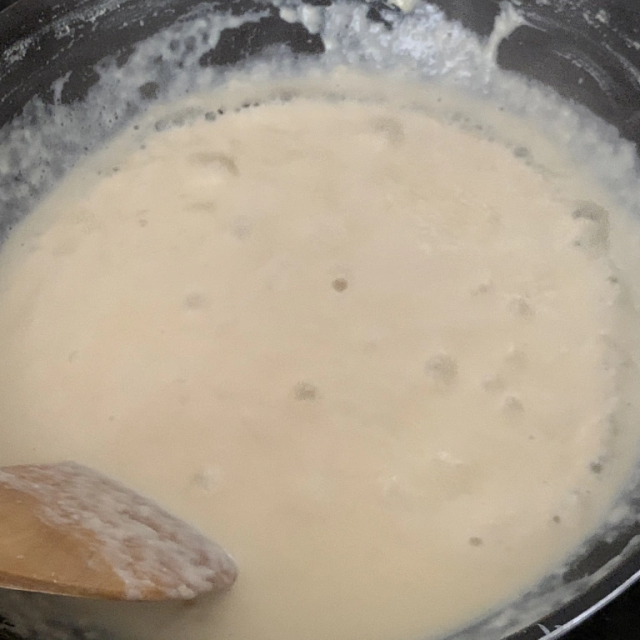

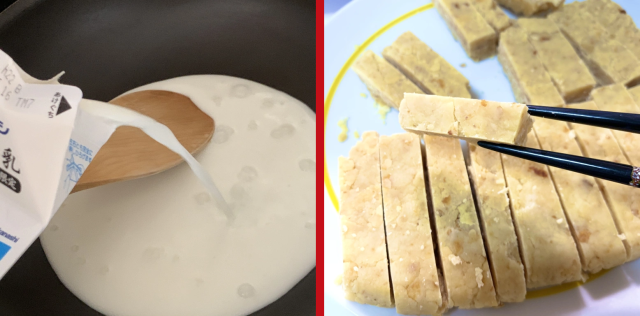

So Ayaka poured her two liters of milk into a frying pan and turned the heat on high. After about five minutes, the liquid around the edge of the pan started to bubble up nicely as it reached a boiling temperature.

But even though Ayaka remembered the so she’d eaten at the museum had a brown color, it hadn’t been burnt. To keep the milk from singeing, she had to keep stirring, and also using the edge of her spoon to scrape along the bottom of the pan to prevent sticking.

At around the 10-minute mark, the consistency of the milk started to change. It reminded Ayaka of yuba (tofu skin), a specialty of Kyoto. Keeping the milk from singeing became a more involved process, as she had to stir more and more diligently. As a reward, though, a sweet smell began to fill her kitchen, almost as though she were baking a batch of cookies.

Thirty minutes in, Ayaka felt like she was in a battle against the boil, constantly moving the spoon so the milk wouldn’t burn. While the recipe for so is simple, it’s a pretty labor-intensive one, and she could see why it was the nobility, with staffs of servants and cooks, who had enjoyed so.

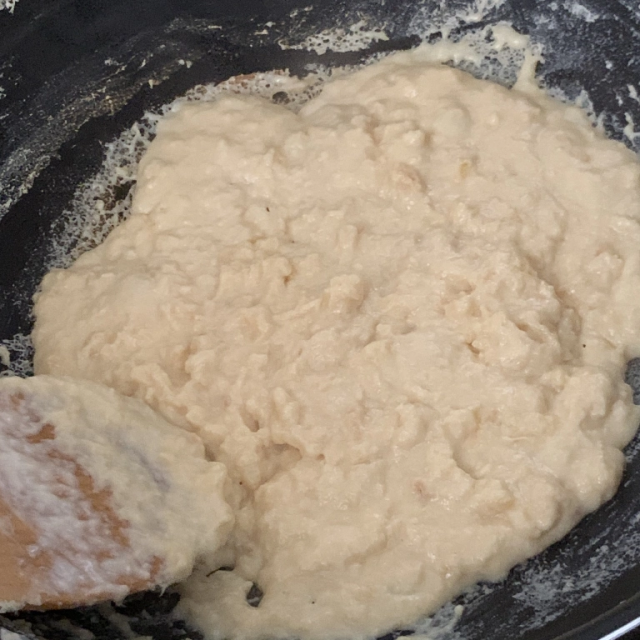

Forty-five minutes in, the milk was now thick, almost like a curry roux.

Tiny bubbles of milk began to leap from the pan and singe her hands, so at this point in the process you’ll want either some long kitchen mitts or a pot lid to shield yourself with. One hour after she’d turned on the flame, the milk was no longer a liquid, but a mysterious mush.

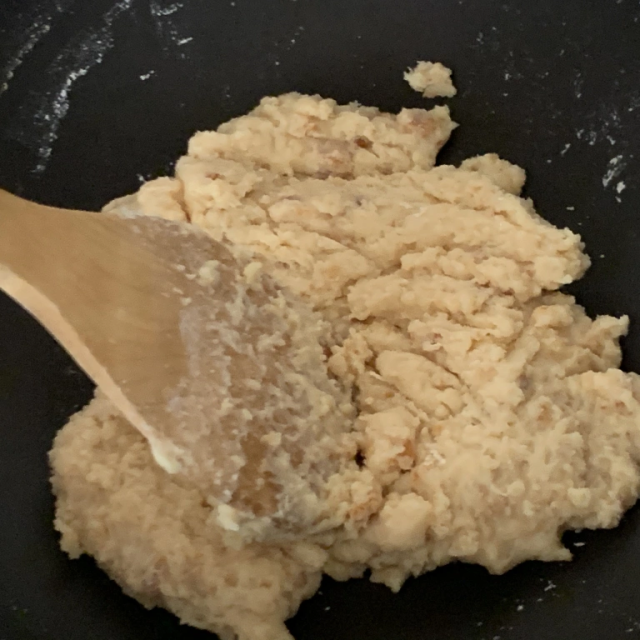

However, this also didn’t match the so Ayaka had eaten at the museum, which was a definite solid, and also darker in color. Turning the heat down to low, she grabbed a spatula and started kneading the so while it was still cooking in the pan.

This seemed to do the trick, as the stickiness started to fade and the milk developed a more uniform consistency. But just when Ayaka thought she was going to be finished…

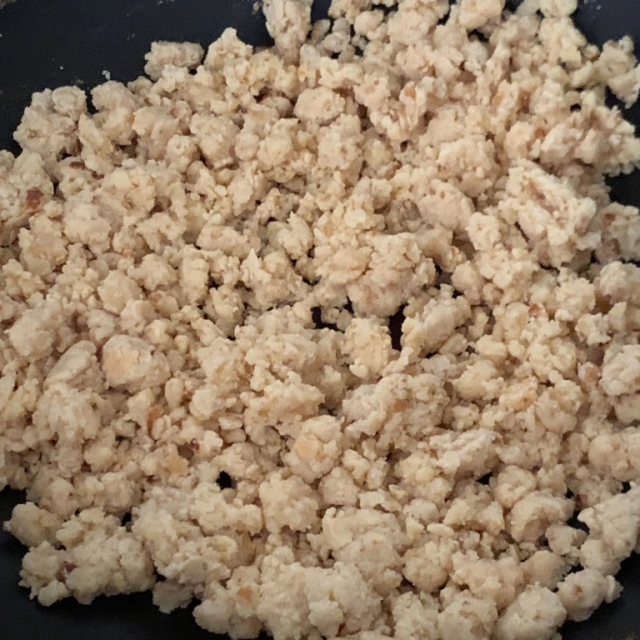

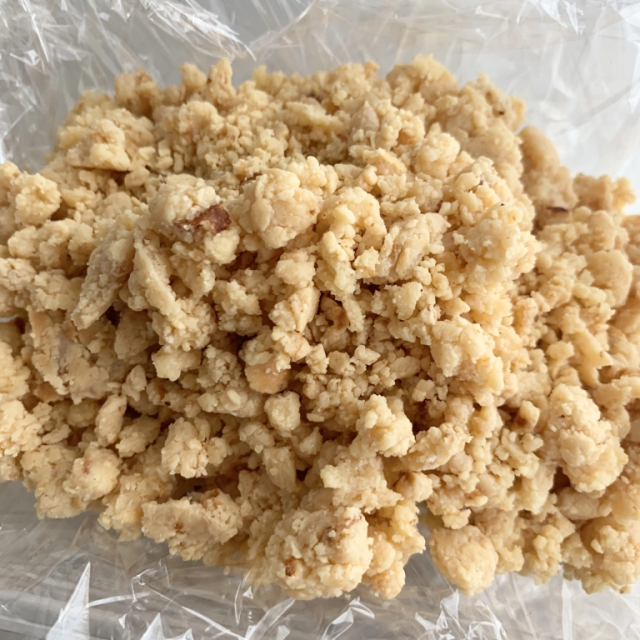

…her so started breaking up into small pieces, almost like ground beef.

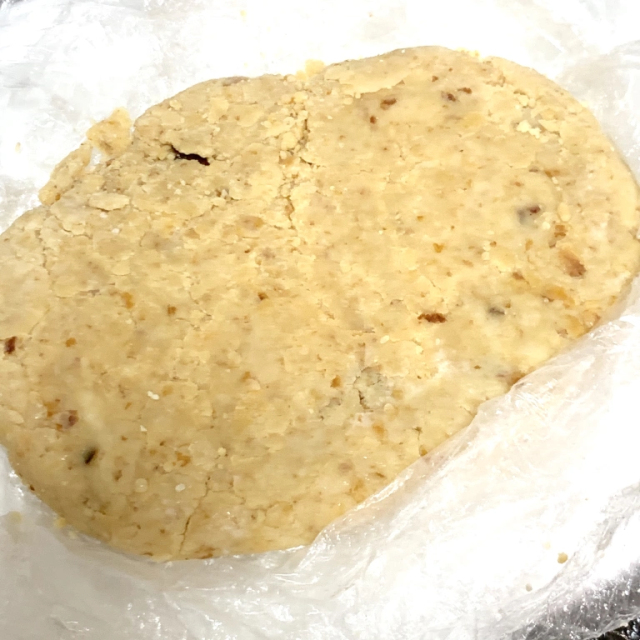

The color, though, was now just like the museum’s. Unwilling to admit defeat, Ayaka wrapped everything in plastic wrap and started forcefully kneading it with her hands.

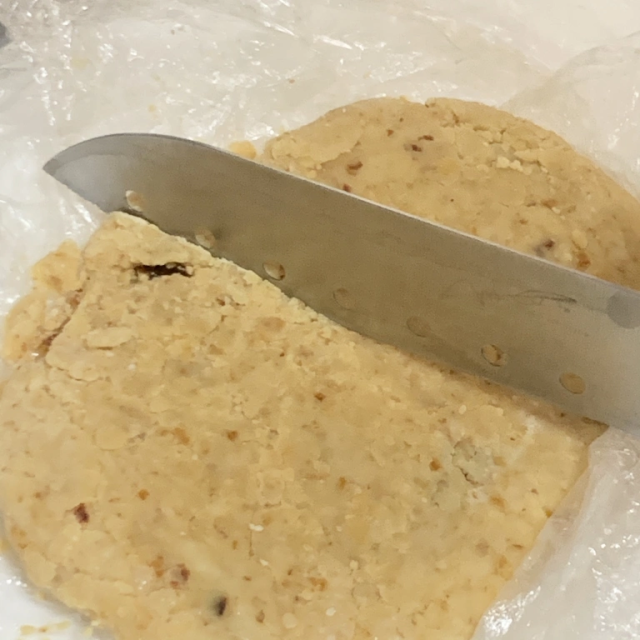

Two hours later, it was time for the moment of truth. Ayaka pulled the package out of the refrigerator, peeled off the wrap, and…

…it looked just like she remembered from the museum! Solid and stiff, the only difference was that hers had a few flecks of dark-colored so that she hadn’t been able to keep from singeing in the pan.

▼ So success

But so is an edible artifact, and it was time to taste it. Once again, this was a perfect match to Ayaka’s memories, with a crisp surface texture leading to a rich flavor reminiscent of a sweet cheese.

Honestly, the so was so tasty that Ayaka felt like she could plow through the whole batch as-is. Still, it’s been a thousand years since so was last in the spotlight, and Ayaka decided to see if she could find a way to spruce it up. Adding salt, soy sauce, and mayonnaise were all detrimental to the eating experience, but two condiments that worked great were yuzu kosho (a spicy, wasabi-like citrus paste) which smoothed out some of the richness, and honey, which amped up the sweet notes and turned the so into a truly indulgent dessert.

▼ So with honey

So in the end, we can see why people in the Heian period liked so so much, especially if they weren’t spending an hour stirring a hot vat of milk themselves. And who know? Maybe so’s resurgent popularity will convince one of Japan’s confectionery companies to mass-produce it, saving us all the trouble if we want another taste.

Read more stories from SoraNews24.

-- Here’s the oldest recipe for Japanese curry in existence, and how it tastes【SoraKitchen】

-- Edo Rice shows you what rice tasted like in the samurai era by continuing centuries of tradition

-- Sake-brewing company produces one-chug wonder: boozy boba in a bottle【Taste test】

© SoraNews24 Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

5 Comments

Login to comment

that person

Wow, I’m going to try this!

Patricia Yarrow

Enjoyed reading this tale of kitchen and historical drama. Well done!

Who knew milk would do this. Now, to find my court staff to do the hour + of stirring.

Strangerland

I may try it as well too. Very interesting - cooked milk solids.

Toshihiro

Hey, this is similar to pastillas in the Philippines, awesome. I hope JT makes an article about Japan's historical survival food recipes, we could really use them right now

Art Vandelay

So So is not so so, So is so good.