If Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) were to have constructed a building that symbolized his life, it would have most likely been haunted by the women he had loved.

First, there was Anna, his mother. When Wright’s parents divorced when he was 17, he had by then been pulled toward Anna’s side of support, his father deemed a financial failure who eventually abandoned the family. Anna placed her hopes and dreams into Wright, her oldest son. “You will be an architect,” she expressed to him at a very early age.

Next came Catherine Lee "Kitty" Tobin, his sweetheart when he apprenticed in Chicago as a draftsman and eventual mother to their six children. They’d married young in 1889 — Wright nearly 22 years old and Catherine just shy of her 18th birthday — much to the anger of their families.

Parenting filled most of Catherine’s time as Wright built his career as a draftsman under the mentorship of Louis Sullivan. By the fall of 1909, Wright’s designs had become famous but he felt that his life had grown stilted and listless. Some, such as architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, believed it was the mental avalanche that comes with a mid-life crisis. Selling off a few of his prized Japanese woodblock prints, Wright set up his family with a year’s worth of salary and then left them behind, flying to Italy with his mistress, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, who’d also left her husband and children behind as well.

Mamah Borthwick has been immortalized in several novels (see Loving Frank by Nancy Horan, The Women by T.C. Boyle) as well as in non-fiction (the excellent Death in a Prairie House by William R. Drennan) but on Aug. 15, 1914, Borthwick had moved into Wright’s home, named “Taliesin.” On that day, a 30-year-old house servant from Barbados named Julian Carlton set fire to the home and killed seven people with a hatchet, including Mamah Borthwick. Wright had been away on work. The press, already for years tracking Wright’s “scandalous” romantic pursuits, covered the story daily.

After Borthwick’s death, a grief-stricken Wright fell into the open arms of Miriam Noel, who’d written sweetly and sympathetically to Wright after the tragedy. Noel lived for a time with Wright in Japan but her extravagant personality mystified the career-driven Wright. Still, he cared for her, and after finally convincing Catherine to divorce him, he married Noel. The couple divorced soon after, though, once Noel’s behavior (she’d grown addicted to morphine and was described as a spiritualist) became too much for Wright to handle.

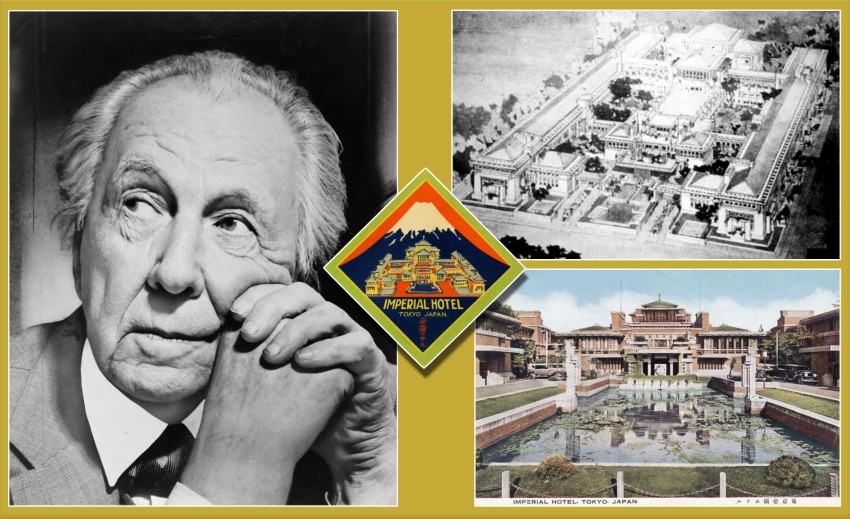

There is one more woman, Olgivanna, but let’s get to why I am telling you all this and not, like I’ve usually done, immediately focusing on the subject’s first trip to Japan. During the years from 1905 to 1923, as Wright struggled to maintain relationships with the women mentioned above, Japan acted as a refuge, a safe haven to his conflict-drenched life. All told, according to scholar Kathryn Smith, Wright spent a total of four chaotic, chopped-up years in Japan, eventually building the Imperial Hotel, one of his most impressive works.

Beginnings

Many writers begin Wright’s lifelong affair with Japan in 1893, when he attended the Chicago International Exposition, also known as the World’s Fair. At the event, Japanese architects had constructed, according to Drennan, “a half-scale model of the Ho-o-Den temple pavilion (originally a part of Kyoto’s Byodo-in), a compellingly delicate 17th-century design… that seemed to emerge organically out of the ground.” Meant to showcase the longevity of Japanese history by combining Heian, Muromachi and Edo-period design, Wright was astonished by its aesthetics.

For years, Wright kept that exhibit in his mind, continuing to collect Japanese woodblock prints of Hiroshige, among other artists. These prints heavily influenced Wright: “If Japanese prints were to be deducted from my education,” Wright wrote in his 1932 memoir An Autobiography: “I don’t know what direction the whole might have taken. The gospel of elimination preached by the print came home to me in architecture.”

Twelve years after viewing the Ho-o-Den exhibit, Wright made plans to travel to Japan. It would be his first time outside North America. Wright, traveling with Catherine and two friends, used the Canadian Pacific Railway, according to scholar Kathryn Smith’s incredibly comprehensive article, “Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel: A Postscript,” and took a train that went directly from Chicago to Vancouver. After the scenic train ride, they left Vancouver aboard the Empress of China steamship on Feb. 21, 1905. Battling seasickness, he hoped to continue collecting rare woodblock prints, but also to absorb as much of the landscape and culture as he could. Wright, continuously fighting nausea, preferred to depart from Vancouver or Seattle, since it took less than two weeks to reach Yokohama. From San Francisco, times were a bit longer: nearly three weeks.

For close to three months, Wright traveled across Japan, hoping to take in the country’s ancient culture. To name a few, Wright visited the Higashi Hongan-ji temple in Nagoya, Kyoto’s Garden of Sanpoh-in, the Ikuta Shrine and the Great Nofukuji Buddha in Kobe. All of it re-energized him, the “shops crammed with curious or brilliant merchandise,” he wrote. “Red paper lanterns on bamboo poles… little cages of fireflies.” To Wright, it was art come to life — “just like the prints!”

“Why are we so busy elaborately trying to get earth to heaven instead of seeing this simple Shinto wisdom of sensibly getting heaven decently to earth?” —Frank Lloyd Wright

The Imperial Hotel

Wright was given the commission to build a “new, larger, and more modern” Imperial Hotel thanks in large part to Chicago banker Frederick W. Gookin, who acted as an intermediary between general manager Aisaku Hayashi. In an October 1911 letter, Hayashi thanked Gookin and wrote that “if [Wright] would not be too radical and would work under reasonable terms he would be the first [choice].”

Gookin let Wright know, excited over the possibilities: “Would it not be possible to retain the feeling and spirit of Japanese architecture and yet construct a building that would be comfortable according to standards and requirements of travelers from the rest of the world? If you would do this you would build a building that would be an object lesson to Japanese and Europeans and Americans alike. And I believe it can be done.”

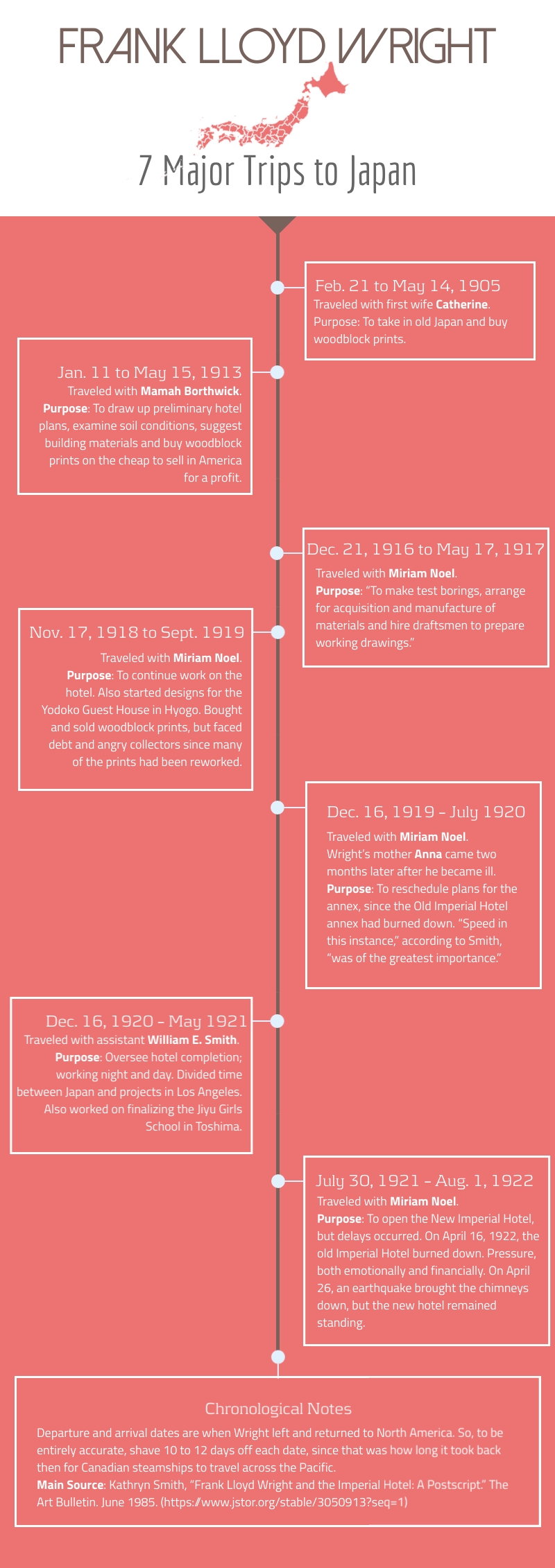

Wright’s next decade could fill three books, but here is a rough documentation of his travels to Japan. Each trip came with additional stress.

According to Eleanor Gibson of Dezeen magazine, Wright worked on 13 other projects in Japan besides the Imperial Hotel. Only two remain standing in full in 2020: The Jiyu Girls School in Toshima, and the Yodoko Guest House built in Ashiya City for a sake brewer named Tazaemon Yamamura.

The Imperial Hotel contract was finally confirmed after a delay in progress due to the death of Emperor Meiji on July 30, 1912. In January 1913, Wright wrote to a friend: “The [Imperial Hotel] is to cost seven million dollars — the finest hotel in the world. Of course I may not get it then again I may — it would mean forty or fifty thousand dollars and a couple of years employment if I did — so wish me luck.”

Over the years living in Japan, Wright not only worked on various projects, but he also took in the culture and began to notice certain subtleties in Japanese people: “I always become painfully aware of our crudity in the more cultured Japanese environment. Their thumbs fold inward naturally as ours stick up and out. Their legs quietly fold beneath them where ours must stick out and sprawl. It could be said that the culture of our civilization is founded upon the silken leg, the shapely thigh, balanced on the high heel. Theirs is founded upon the graceful arm, the beautifully modelled breast and the expressive hand. The finely moulded leg rising from the shapely shoe indicates our heaven. The finely modulated breast and arm and expressive hand indicates theirs. There is a difference.”

Of course, Wright also commented extensively on Japanese structures, lauding their religious minimalism: “… the truth is the Japanese dwelling is in every bone and fibre of its structure honest and our dwellings are not honest. In its every aspect the Japanese dwelling sincerely means something fine and straightway does it. So it seemed to me as I studied the ‘song’ that we of the West cut ourselves off from the practical way of beautiful life by so many old, sentimental unchristian expedients? Why are we so busy elaborately trying to get earth to heaven instead of seeing this simple Shinto wisdom of sensibly getting heaven decently to earth?”

Disaster strikes

Still, Wright suffered greatly while in Japan, falling ill several times — especially near the end of the project. In February 1921, he wrote to his daughter how he’d started to feel his age: “I am never very well here but my Welsh ire will wear through… once upon a time I never could strike the bottom of my physical resources — but now I find that very grey hair and fifty-three years — indicate something that I will have to pay attention to — in this [Tokyo] climate — which is the worst in the world, I believe.”

Yes, Wright disliked the humidity, which can bring many people a sense of dullness, but he did manage to schedule most of his trips so that he could at least enjoy viewing the sakura (cherry blossoms) in March or April.

Wright traveled back to the United States in July 1922, never again visiting Japan. Back in America, he reflected a month later to a friend how incredible the journey had been: “My experience in the building of the great building in Japan has taught me how difficult of realization my ideal in Architecture is. I had to come to close grips with everything in the field as the whole affair including furniture was made by my own workmen ‘on the job'. I realize how inadequate my superintendence has always been — how rash I was to aim so high and how much my clients had to give in patience and forbearance to get the thing which in the beginning they did not really want — perhaps.”

On Sept. 1, 1923, according to Smith, the Imperial Hotel officially opened its doors. But on that exact same day, and just before the ceremony’s luncheon, the 7.9 magnitude Great Kanto Earthquake shook Japan, killing over 100,000 people and demolishing thousands of buildings across the region. For days, Wright heard conflicting reports as to whether the hotel, his “battleship” he liked to call it, survived. Eventually, he received a telegram from Aisaku Hayashi, the man who’d first brought Wright into this decade-long journey. The message was music to Wright’s ears: “Imperial stands, square and straight. Congratulations.” Indeed, despite some minor damage, the hotel would end up being used as an emergency hospital in those tragic days and weeks after the quake.

After the mighty success of the Imperial Hotel, Wright, now in his 50s, was able to move on from the drama and tragedy of his earlier years and toward a new chapter in his life, meeting Olga Ivanovna Lazovich, or Olgivanna, who was three decades his junior. She would act as his muse as he entered the third act of his career: ''Just to be with her,” he wrote in 1932, “uplifts my heart and strengthens my spirits when the going gets hard or when the going is good.'' They would remain married until his death in 1959.

Olgivanna would eventually support Wright during his most famous American works, such as Fallingwater house built partly over a waterfall in southwestern Pennsylvania and the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Wright will always have his share of fans and critics, but his life and career was never an attempt to please everyone. More than that, he wanted to be as true to himself as he could. “Early in life," Wright once said to a good friend, "I had to choose between an honest arrogance and a hypocritical humility... I deliberately choose an honest arrogance, and I've never been sorry.”

Our next installment of the Japan Yesterday series will feature a young Douglas MacArthur's visit to Japan 40 years prior to his historic WWII-ending role.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

Volume 2 (September 2019 – present)

- J. Robert Oppenheimer Father of the Atomic Bomb Visits Post-War Japan

- Alexander Graham falls asleep meeting Emperor Meiji

Volume 1 (November 2018 – May 2019)

- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth Visits Japan

- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

- Audrey Hepburn Casts a Spell Over Post-War Japan

- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age. His work has appeared in Politico, the Atlantic and American History Magazine, among others.

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

3 Comments

Login to comment

Laguna

Parr-san, thank you for your series. I gobble each up.

Sh1mon M4sada

Genius! If anyone get a chance, go see his other works, like Falling Water, utterly spellbinding.

@BigYen - agreed, Japan doesn't know how to conserve. I am dismayed by the thoughts of bulldozers demolishing the brick armament factories in Hiroshima that survived the blast.