Ever since the formal end of World War II, American presidents had tried to be the first to visit Japan while in office. In April 1946, it was reported via the International News Service (INS) that Harry S. Truman was considering a brief July visit to Occupation-era Japan since he had already been planning a trip to the Philippines to commemorate their independence.

“No arrangements have been made at all as yet for such a trip,” announced Charles G. Ross, Truman’s press secretary at the time. “And plans are extremely tentative…he might go anywhere.”

Truman ended up going nowhere that summer, due to domestic legislative issues and major coal and rail strikes.

In June 1960, Dwight D. Eisenhower did touch what is now deemed Japanese soil — Okinawa. At that time, the island was under American rule (until 1972) and Eisenhower had already canceled prior plans to visit Tokyo after major anti-American demonstrations (Anpo protests) connected to the controversially negotiated security treaty. Protesters had burned effigies of Eisenhower and then-Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, who soon after resigned, and had surrounded press secretary James Hagerty’s car, known later as “The Hagerty Incident.”

As Okinawa historian Robert D. Eldridge documented, Eisenhower completed a “two-hour-plus visit” of Naha before leaving for less angered crowds in South Korea.

There was talk in January 1962 by newspaper journalist Keyes Beech of John F. Kennedy visiting Japan in November of the same year, with later reports saying “early 1963.” But after the complications with the Eisenhower visit, officials around Kennedy were concerned, their fears remaining even after his brother Robert Kennedy visited Japan in February 1962. One obstacle the president wanted out of the way was sour relations between South Korea and Japan.

As Beech wrote back then: “Japanese leftists vowed to block relations between [Japan] and the rigidly anti-Communist military junta now ruling South Korea.” Unfortunately for Japan, those fears remained throughout Kennedy’s presidency. In October 1963, the Associated Press reported that, “Kennedy may visit Japan and other island nations in the Far East in December [1963].” Before plans could even be made concrete, Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963.

As for Lyndon B. Johnson, in January 1965, Prime Minister Eisaku Sato visited Washington D.C., inviting Johnson to visit Japan. The Los Angeles Times reported Johnson as being “pleased by the idea…but no dates were set.” As the war in Vietnam escalated, Johnson stayed, and his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, reached Japan in late December 1965. Talking to Sato as well as Emperor Hirohito, his 18-hour visit was largely free of protests.

Humphrey’s brief stop — part of an Asian tour — may have slightly offended members of the Japanese foreign ministry. When Johnson, in October 1966, planned a packed six-country trip to countries including South Korea and New Zealand, Kinya Niiseki, a spokesman for Japan’s foreign office, told the media that “the government would prefer any visit from President Johnson to be an arranged matter — ‘a thing in itself’ — rather than something incidental to a sweep through Southeast Asia.” Johnson never found the time to put together something more respectful.

Next came Richard M. Nixon, but, again, the conditions didn’t seem right.

Nixon had been formally invited to visit Japan during the Expo ’70 world’s fair in Osaka, but as Beech reported in July 1969, even though “Japan is today the world’s third largest industrial power and supposedly America’s No. 1 ally in Asia…” with a government that was “conservative and pragmatic — like Mr. Nixon…the paradox is that the President of the United States cannot go to Japan because the risks, political and in terms of the President’s personal safety, are too great for either country.”

Beech mentioned that the Zengakuren student movement, “a coalition of left-wing elements including socialists, Communists and labor unions, is even more militantly far out today than it was in 1960.”

Still furious about Okinawa and the U.S.-Japan security treaty, the Zengakuren was a large enough presence to dissuade Nixon from coming. Later, according to Japan scholar Gerald L. Curtis, when Nixon sent national security advisor Henry Kissinger on a trip to Beijing in July 1971, the act “embarrassed” Prime Minister Sato, and caused confusion when dealing with policy issues.

Nixon would go on to embarrass himself via the Watergate scandal, and in August 1974 he resigned from the presidency. Taking his place would be his vice-president — 61-year-old Gerald Rudolph Ford, a 6-foot, 185-pound former college football player who’d served on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific as an assistant navigation officer.

Security and protests

At 3:27 p.m on Nov. 18, 1974, Air Force One, after a 20-hour flight and fierce turbulence, landed at Haneda Airport. Out came a travel-weary Gerald Ford, accompanied by the protocol-required 21-gun salute. With him was secretary of state Henry Kissinger.

Ford and Kissinger waved to the crowds of people, around 2,700, with Japanese and American flags in hand. According to reporter James Wieghart of the New York Daily News, they were “escorted to a green-and-white helicopter bearing the presidential seal…The arrival ceremony took only 11 minutes.”

There was a reason for this brevity, and it had a lot to do with the 37,000 protesters in the Tokyo area. Japanese security officers did not have the American president in a public space for long.

As Wieghart wrote, police had “seiz[ed] 120 iron clubs and helmets in raids on four leftist hideouts in the Japanese capital.” Police across Japan had also reported to journalists that “119,000 persons…took part in demonstrations protesting [Ford’s] visit.” Around the airport alone, over 200 arrests were made as helmeted police and protesters collided. In perhaps the largest political statement, as UPI wires and the Washington Post reported, “About 3.35-million workers from 59 unions called protest strikes for today against Ford’s visit, including a nationwide railroad shutdown.”

But this social unrest was unseen by Ford, who seemed to declare this absence of tension as a sign of peace and welcome. Writing in his autobiography, A Time to Heal, Ford stated that: “Even though we’d been warned that my arrival might spark violence, there was hardly a demonstrator in sight.”

This was Japan’s plan all along — to deliver a vision of what U.S. newspaper wires described as an “overwhelmingly friendly” country.

“I thought the trip was important…The Japanese had been shocked by Nixon’s failure to inform them of his overtures to the People’s Republic of China in 1971 and 1972. They had been equally upset by his subsequent devaluation of the dollar, and for some months afterward their attitude toward the U.S. had been tinged by suspicion and doubt…even though the Japanese…trip was more ceremonial than substantive…I looked forward to a visit that would symbolize the special relationship that existed between our two countries.” – Gerald R. Ford

Specific precautionary measures were made to ensure Ford was kept safe. As various international dispatches reported, “Japanese authorities have been working closely with an advance party of United States Secret Service agents since Nov. 5. Well in advance of Ford’s arrival, his Secret Service guard moved into the guest house where he will stay.”

As of 1974, 33% of Japanese voters ticked the box of either a Socialist or Communist party candidate, and protesters didn’t want Japan to come even further under America’s capitalistic and militaristic policies, especially under the then-unpopular Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka, who dispatches explained was “in political difficulties because of raging inflation and charges of corruption in his administration.”

From Ford’s perspective, he knew the line he needed to walk: No controversy and no mistakes.

Ford’s visit was meant, Wieghart wrote, “as a symbolic effort to show the Japanese that the U.S. has not forgotten them in establishing diplomatic relations with their giant neighbor, China.”

As Ford put it later in his autobiography, “…I thought the trip was important…The Japanese had been shocked by Nixon’s failure to inform them of his overtures to the People’s Republic of China in 1971 and 1972. They had been equally upset by his subsequent devaluation of the dollar, and for some months afterward their attitude toward the U.S. had been tinged by suspicion and doubt…even though the Japanese…trip was more ceremonial than substantive…I looked forward to a visit that would symbolize the special relationship that existed between our two countries.”

Meeting Hirohito

Ford recovered that night in the Akasaka Palace presidential suite. The next morning, Ford as well as Kissinger were escorted out to the courtyard. As Ford’s itinerary shows, the event was to be rigidly formal. When Ford met Hirohito, for example, there was a specific note stating that “According to Japanese Protocol, it would be inappropriate to introduce Secretary Kissinger to the Emperor at this time.”

The moment was indeed historic, and moved several members of the press who had been Ford’s age during World War II.

One of them was Frank Kane, who covered the event for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Kane, like Ford, graduated from the University of Michigan and served in the Navy. In his write-up, he assumed that Ford, like himself, “hated” Emperor Hirohito during their years in the armed forces. “[Hirohito] is someone who, when Ford and I were a lot younger, ranked right up there with Adolf Hitler in American eyes. And it was really something to see him chatting with an American President in a palace courtyard in Tokyo and then standing next to the President while a Japanese band played the Star-Spangled Banner and the Japanese national anthem.”

Unplanned was the band's impromptu playing of the University of Michigan’s fight song, “The Victors.” Kane couldn’t help but quote another UM graduate working for the Chicago Daily News, Peter Lisagor: “[When the fight song played] it quickened the blood of every Wolverine present — all two of us. I told Peter to amend that to three, to include me.”

If Ford had indeed “hated” Hirohito, he made sure to suppress those past feelings in his autobiography. “The Emperor is head of state in name only; he does not discuss politics or substantive issues, and I had been told that it would be difficult to carry on an extended conversation with him. But we got along fine. A noted marine biologist, the Emperor had just completed his fourth book on the subject. He enjoyed talking about it, and I think he appreciated the fact that I’d done some homework in the area myself.”

During this day, which later would include dinner at the Imperial Palace, Ford extended an invitation to Hirohito to visit Washington D.C., which he did in October 1975. Hirohito had previously visited Nixon in Alaska in 1971.

It’s worth noting that after Hirohito visited Ford in 1975, he was grilled by Japanese newsmen for sounding to the American press as if he’d been some guiltless “innocent bystander” during the war.

Doing as Instructed

After being driven to the Imperial Palace and spending an hour exchanging gifts and pleasantries with the emperor and empress, Ford was driven back to Akasaka Palace, where he changed into a “business suit” and prepared for the arrival of Prime Minister Tanaka.

Ford knew that Tanaka was in hot water with Japanese voters, and stated as much in his autobiography. “A burly, aggressive man whose nickname was ‘Tiger,’ Tanaka never let diplomatic niceties stand in the way of blunt speech. Although our relations were formal and correct, he was not the kind of man to whom I could warm up easily.” Tanaka’s time as prime minister came to an end less than three weeks after meeting with Ford, amidst accusations of profiteering via shadow companies.

Over the next 36 hours, Ford’s schedule was packed with mainly ceremonial or symbolic events, as his motorcade went back and forth between the Imperial Palace and the Akasaka Palace. Fortunately for Ford, it wasn’t all formalized mingling. On Nov. 20, from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m., Ford and company headed over to the Budokan, where he and around 8,000 press and approved spectators were given an exhibition of judo, kendo, naginata (a Japanese version of the glave or European polearm), gymnastics and volleyball. Ford’s itinerary that day prepped him on the history of Japan's martial arts. The naginata, it was noted, “is one of the oldest weapons in Japan,” and “is considered a splendid method of teaching respect for traditional etiquette and spiritual growth.”

On Nov. 21, after planting a “nine-foot dogwood tree” in the Akasaka Palace courtyard, Ford was given an official break from political engagements. You could call it his one day of cultural sightseeing. He and Kissinger flew by helicopter to Haneda, then boarded Air Force One. After a quick flight to Osaka International Airport and another 20-minute helicopter ride, Ford’s motorcade brought the president to Kyoto’s Miyako Hotel. Reporters counted about 200 protesters near the hotel and around the Imperial Palace, but they were kept at a distance. Ford could ignore them, but he couldn’t ignore the fact that Kyoto’s socialist-leaning governor at the time, Torazo Ninagawa, had rejected an invitation to meet Ford.

All afternoon, Ford took in the sights: the Imperial Palace, Nijo Castle, Kinkakuji and the Pond Garden. As always, Ford’s itinerary maker was ready for photo suggestions: “It is suggested that you stop on the second bridge, Kiaki-Bashi, to view the fish swimming in the pond and afford the press an opportunity for photographs. If you clap your hands, the fish will come into view in the vicinity of the bridge.”

Sure enough, Ford did.

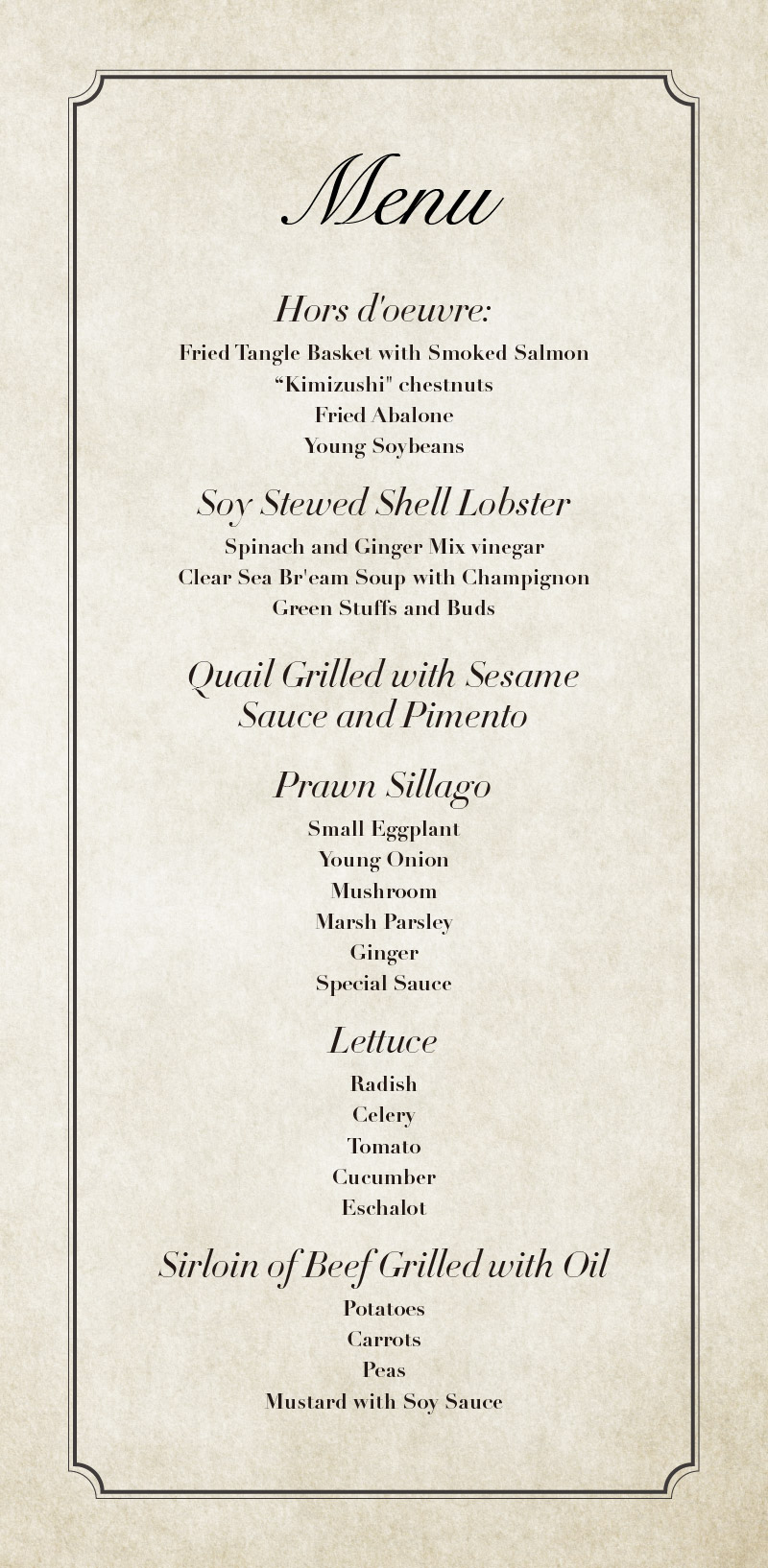

That night, Ford perhaps faced his greatest challenge — a traditional Japanese dinner. They chose the internationally known Tsuruya Restaurant. The menu for the ten-course meal was as follows:

Faced with the daunting task of using chopsticks properly while not accidentally offending the chef or the guests around him, Ford studied the extensive notes given to him. It was a crash course in Japanese dinner etiquette, and the meal’s cultural specificities impacted him enough that he decided to reproduce the notes in nearly their entirety in his autobiography:

- 7:10p.m. – Dinner begins.

- You will be served on a very low chair or cushion at floor level with a small back. It is customary to cross your legs, and you may stretch your legs out and change your position frequently if you desire. Chopsticks will be used exclusively during the dinner, and it is customary when you have a piece of meat or fish to eat, rather than cut it, you lift the entire piece and take a small bite, returning the remainder to your plate. Chopsticks should never be left in the plate or bowl but returned to the resting block in front of your service.

- There will be Geisha girls at the meal who will come in and out and at times sit next to you in the serving of the meal. It is appropriate for you to talk to them. They will dance at the conclusion of the meal. This is a ten-course dinner served in traditional Japanese style.*

- Custom provides that no one should ever pour his own cup of sake. To do so is a sign of sadness. You may, however, pour someone else’s cup, which is a sign of friendship. Whenever a Geisha girl or another guest fills your cup, you should lift the cup while it is being filled and take a sip before putting the cup back on the table. Whenever the cup is empty, it will be refilled, so it is advisable not to “bottom up” on each occasion.*

Such was life for American presidents traveling abroad. Every five minutes, they were directed somewhere else, told to shake hands and greet dignitaries in this order, told to pause for pictures here, engage the crowd here, eat this way, talk to guests at this time, and so on.

“Everything went according to plan,” wrote Ford of his trip to Tsuruya, the only somewhat unpredictable moment coming when “without warning, photographers appeared.” Their timing caught Ford talking to the geisha, as he’d been instructed. “Wait until Betty [Ford’s wife] sees the pictures of me sitting with those Geisha girls, I thought.”

The following morning, Ford flew to Seoul, and with that trip, a 14-page itinerary. He was president, yes, but his every move would continue to be documented and reported.

Our next Japan Yesterday will feature Queen Elizabeth’s trip to Japan in 1975.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

Volume 3 (January 2022 – present)

Volume 2 (September 2019 – July 2021)

- William Elliot Griffis resists temptation in feudal 1871 Japan

- Marian Anderson sings for the Empress of Japan

- Robert Kennedy confronts communist hecklers at Waseda University in 1962

- Commodore Perry’s black ships deliver a letter to Japan in July 1853

- The story of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s trip to Shuri Castle in 1853

- Japanese journalist witnessed the death of Malcolm X

- Muhammad Ali fights Antonio Inoki at the Nippon Budokan in 1976

- Eleanor Roosevelt visits ‘burakumin’ and Emperor Hirohito in 1953

- Charles and Anne Lindbergh fly 7,000 miles to Japan in 1931

- A young Douglas MacArthur visits Japan in 1905

- J. Robert Oppenheimer father of the atomic bomb visits post-war Japan

- Alexander Graham Bell falls asleep meeting Emperor Meiji

- Frank Lloyd Wright designs Japan’s Imperial Hotel during a midlife crisis

Volume 1 (November 2018 – May 2019)

- The ‘Sultan of Swat’ Babe Ruth visits Japan

- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

- Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

- Audrey Hepburn casts a spell over post-war Japan

- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

- Russia’s Nicholas II is scarred for life in 1891 Japan

Patrick Parr’s second book, One Week in America: The 1968 Notre Dame Literary Festival and a Changing Nation, was released in March 2021 and is available through Amazon, Kinokuniya and Kobo. His previous book is The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age, now available in paperback. He teaches at Lakeland University Japan in Tokyo.

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

1 Comment

Login to comment

Jtsnose

Beautiful . . . when diplomacy works!