Forty years -- 40 years for one sword, 40 years to master one single technique. Half a lifetime for one katana. That's the time Shimpei Kawachi's father took to learn the method of "utsuri," which translates to "reflection" or "shadow of the hamon" (blade pattern).

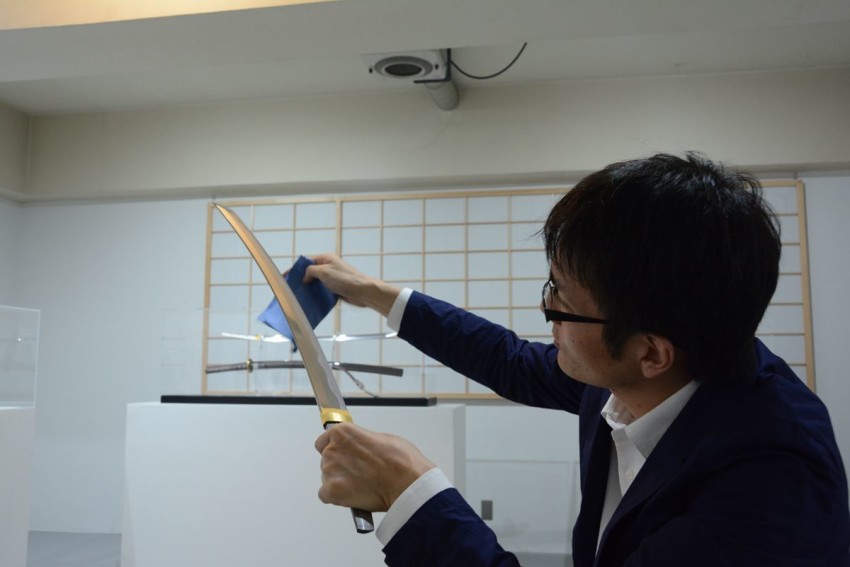

Hold the sword blade against good lighting, and if there is a distinct swerving line appearing down the center of the sword, it is manufactured using the "utsuri" technique, says Kawachi, who is the 16th generation of a famous Japanese sword artisan family. "My father was working really hard and now he is the only person in Japan able to create this very special pattern," he explains.

This technique, applied to Japanese sword production until 1600, had been presumed impossible to recreate after this age and would be extinct in Japan without Shimpei's father.

It's now the family's vocation to keep this ancient art alive by organizing regular exhibitions. "My goal is to protect the technique and protect the artwork and spread it around the world through an artistic point of view," says Shimpei Kawachi. The family has got the manpower for that. Three out of the four brothers are engaged in the sword business. One can tell that Shimpei is a true expert in his field. He just needs a quick glance at the blade to be able to tell when it was made, where and by whom. "Every sword tells me a story," he says. While his brothers are still active as swordsmiths, Shimpei is now focusing on business development. With his own company, "Studio Shikumi," he says he is trying to "keep something Japan cannot keep."

Before becoming self-employed, Kawachi used to work as a researcher at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno. Regularly, he got inquiries from people who had inherited cultural assets and wanted their artwork to be preserved. But he had to reject those requests, "because the pieces had no monetary value" - even though the memorable value for these families was priceless, regardless of the market value. By dealing with these visitors' requests, he came to think that managing and preserving cultural assets could actually be a niche in the market. That's when he started exhibiting and selling private objects. After some time he detected a special demand for swords. Very often those inquiries came from foreigners, in many cases from Hong Kong, people, who want to expand their art collection.

Some customers, though, hesitate to buy a sword – without doubt, it is a deadly weapon – but when you hear Kawachi talking about it, it transforms into an art piece and loses its threat. Historically, swords have had a very ambiguous character. In ancient times, a katana was considered both a weapon and a sacred item worshipped in the shrine. It is also said that a sword guards your spirit and is a popular gift for the birth of a baby as a symbol of protection.

If you have the opportunity to attend a traditional Japanese wedding, you may notice that it is still common for the bride to hide a small knife under the thick layers of her kimono. No, it's not so she can defend herself from her husband, but in olden times, it was to stab herself in case of divorce in order to avoid the shame and humility of returning to her family. Be assured: This custom is no longer carried out – these days women keep their swords in the storage room and just take them out every year at New Year to admire them.

A katana has its price. An "utsuri" sword, manufactured by award-winning swordsmith Kunihira Kawachi, Shimpei's father, costs several million yen. However, one has to take into account that the very complex production for one single item takes about one month and requires incredibly repetitive reforging of steel and polishing to bring out a subtle wave-like pattern to the blade. It is a constant pursuit of excellence, beauty and perfection of the material.

There are around 200 sword artisans in Japan today, but only about 10 can make a living out of it. After World War II, many artisans who were involved in the blade-making process, lost their job and had to adapt their profession to present demands. Some of them are now making "jizai okimono," which are realistically shaped figures of animals made of steel. Their bodies and limbs can be moved like real animals. Some of these movable figures can be integrated into daily use and serve as paper weights or incense holders.

It shows that Japanese crafts are trying to create a link between traditional art and modern technology. One project which perfectly demonstrates that is Studio Shikumi's collaboration with Rinkak, a 3D printer company. The collection features various objects such as a sword, 100% handmade, with an acrylic scabbard, produced by a 3D printer. It took Kawachi six months to program the printer, now being ready for serial production.

Another outstanding series of objects, which is truly unique in design, aesthetic and technology is the "urushi" (lacquer) series, which combines Japanese lacquer and 3D techniques. The collection includes a drink vessel set, small mirrors, bowls and a flower vase. The lacquer shines through the outer layer of the bowls, like fog in the mountains, and the design of the mirror reminds one of the pattern of a kimono. The basics are done by the 3D printer, while the finishing though is 100% done by artisans – using the technology similar to the iPad polishing.

It doesn't take Kawachi long to answer why one should invest a significant amount of money into his objects. "It deepens your life," he says. It is common thinking that drinking cheap sake from a cheap glass tastes the same as if you were drinking it from a precious container, he explains. "It might be true. But you can't feel the spirit of the craftsmanship." After all, it's a lot about "kimochi" – it's all about the feeling.

Hamon Gallery: http://hamon.co.jp Website of Kawachi Shimpei: www.studio-shikumi.jp 3D Printer company: https://www.rinkak.com/us/urushi?hl=en

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

6 Comments

Login to comment

Iowan

Good article for a good story.

nandakandamanda

Agreed, except for the implied monopoly on utsuri in the first paragraph.

At least one other Japanese swordsmtih is creating utsuri today. The problem is, he told me, that there is an unwillingness 'by some' to share and spread their understanding and techniques to the wider sword smithing community.

sf2k

basically if you don't share the knowledge it's not going to survive

Fox Sora Winters

@Oirik: It wasn't banned outright, but harsh restrictions were placed on production. There's a very tight limit to the number of swords these artisans can forge each year. They need a license to forge the swords, and I believe they need to be licensed to sell them as well. As for the swords being worn in parades: they're ceremonial. We do it in Britain as well. Most militaries around the world have ceremonial swords for parades and the like. Many naval officers are required to wear a ceremonial Sabre at parades and similar events, as an example.

It's a fascinating article. I'd love to see a sword that bears Utsuri. I've seen many with artificially created hamon (usually laser etched), I even own swords like that, but I'd like to see the real deal, if only once.

Triring

The gunto worned by IJA of WW2 were also ceremonial swords. Being able to hack 100 heads with them was a complete myth.