It all started on April 27, 1891, when Tsesarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich II — heir to the Russian throne then held by his father, Alexander III — stepped onto the docks at Nagasaki Bay. The mustachioed 22-year-old prince wanted to take in Japanese culture before heading to Vladivostok to acknowledge the beginning of construction for the Trans-Siberian Railroad. It was to be a peaceful, month-long trip, but as one eyewitness wrote in an 1891 letter to the British newspaper The Observer, “it was rumored that the objects of his visit were sinister and unfriendly — that [Nicholas] really came to spy out the weak points of the country.”

It’s unlikely that Nicholas II — then a young man on a world tour with little political experience — had any kind of serious intention of “spying,” and at the time, Emperor Meiji did not believe it, either. Rather, Meiji hoped to impress Nicholas with Japan’s recent progress in industrialization and curry favor with the man who was next in line to the Russian throne. By gaining Nicholas’s trust, Meiji could then hold more considerable leverage as Japan continued to renegotiate treaties that had been deemed outdated, “unequal” and unfair.

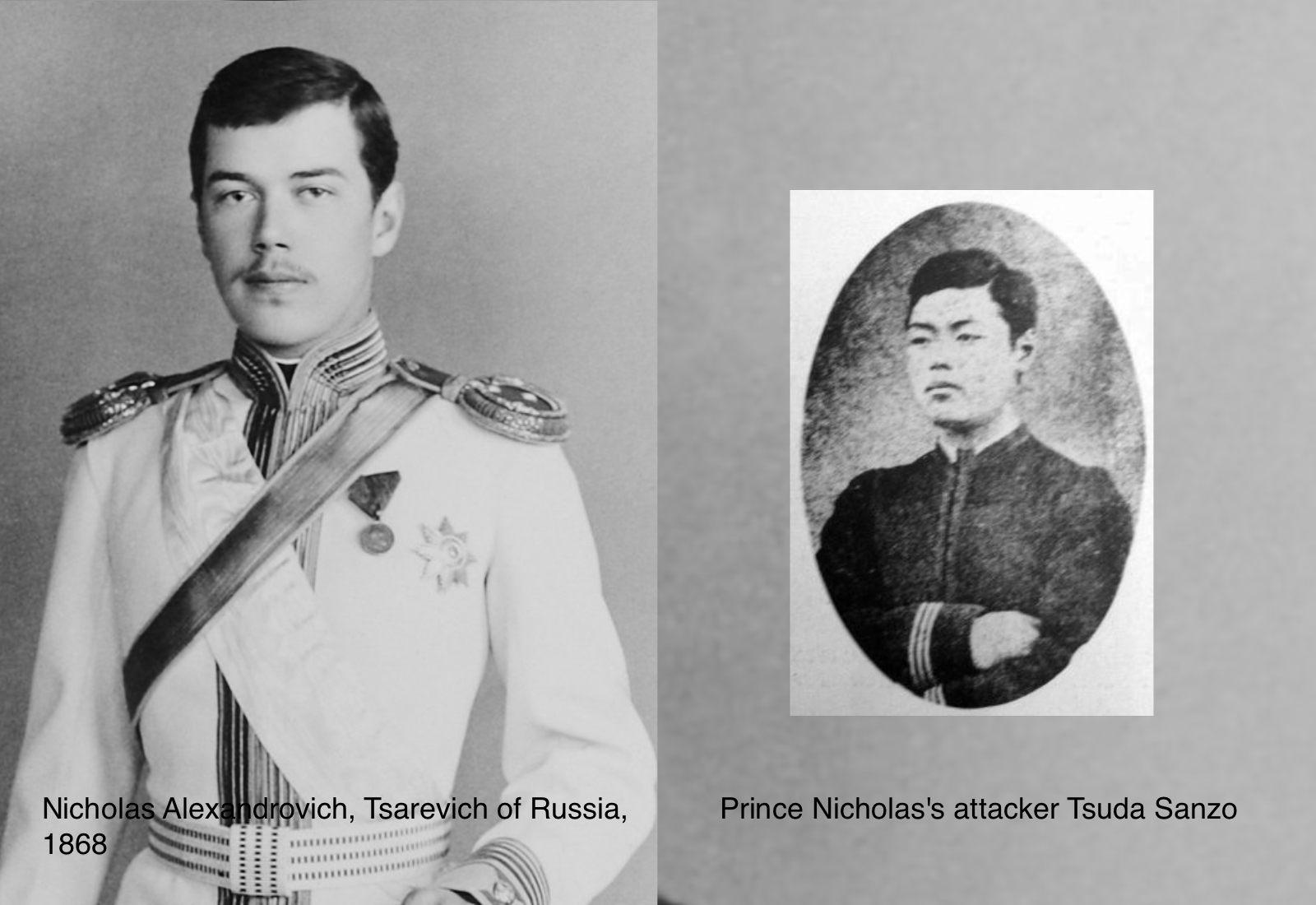

Most of the nation fell into line with the emperor’s intentions, but like all countries, potential fanatics rest below a tense surface. One of them, a 36-year old policeman named Tsuda Sanzo, believed Nicholas was a spy and there was to be no good of him seeing a rapidly developing Japan. Sanzo’s frustration may very well have been connected to a growing concern for Japan’s national identity. Here his country sat, saddled by lopsided treaty deals that handcuffed his country and left them at the mercy of others. Gone were the years when a closed Japan made deals and remained largely unaffected by other outsiders.

To add to the tension, Japanese newspapers continued to print articles filled with doubts and paranoia. Why, for example, did Russia believe they were entitled to the long Sakhalin Island directly north of Hokkaido? Won’t Russia attempt war to secure a Pacific port that can remain open longer than six months a year? Doesn’t it seem as if Russia is positioning itself to take Korea? These questions filled the minds of many, including Sanzo, a former samurai who had fought in the Satsuma Rebellion on the side of the emperor.

Nicholas remained in Nagasaki for a few days. According to Russian writer Alexander Mescheryakov, Nicholas visited with “young Russian naval officers… each of them [managing] to acquire a Japanese ‘wife.’ In Japan of that time, ‘marriage contracts’ were accepted for a certain period of time.”

As if to double down on his desires, Nicholas’s book-of-choice while traveling happened to be "Madame Chrysantheme," a best-selling French novel written in 1888 by Pierre Loti. The novel, according to "The Chrysantheme Papers" author Christopher Reed, is a “fictionalized diary [describing] the affair between a French naval officer and Chrysantheme, a temporary “bride” purchased in Nagasaki.” It appears that if Nicholas II were a spy, he’d have been quite distracted.

In those first few days in Nagasaki, according to Mescheryakov, Nicholas walked along the shore, “rode a rickshaw, bought souvenirs, and even spent some time” deciding whether or not to get a tattoo. Soon enough, two Japanese tattoo masters (Nomura Kozaburo and Matasaburo family name unknown) were requested to board Nicholas’s ship, christened the Pamiat Azov. Perhaps encouraged by Prince George of Greece — his friend and current travel companion who was tattooed also, Nicholas asked for a tattoo of a dragon to be inked onto his top right forearm. Although his decision was thought to be a secret, the news quickly spread across the country that an “image of a dragon with a black body, yellow horns, a red belly and green paws” could now be found on the arm of the next Russian ruler.

On May 4, George and Nicholas, now newly branded, popped in on a ceramics exhibition and visited a Shinto shrine, showing a respectful politeness as they ate and attempted to understand the customs. By nighttime, however, they headed over to a restaurant called Volga, and the owner offered the second floor along with “two girls.” The young men obliged and skulked back to the Azov at around 4 a.m.

Nicholas left Nagasaki by boat and decided to pay a quick visit to Kagoshima. Odd rumors had started to spread that Nicholas somehow had returned to give back Saigo Takamori, who’d famously led the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877 but had reportedly killed himself. Hopeful Takamori devotees wanted to believe that instead of suicide Takamori “took refuge in the vast Russian expanses.” Untrue of course, Nicholas was still able to satisfy his desire to learn from the old samurai culture. At least 170 samurai greeted Nicholas dressed in full body armor. One samurai, Shimazu Tadayoshi, showed Nicholas how to fire an arrow while on a galloping horse. All of this, reported in the news, would have only inflamed Sanzo, who believed Nicholas should have started his trip respectfully by bowing before the emperor in Tokyo.

On May 8, Nicholas’s ship docked at the Kobe port. A train ride to Kyoto followed, and Nicholas and George were soon greeted with Greek and Russian flags, and a newly built arch with the Russian greeting of “желанный” (“Welcome”) across it. They watched kemari, a traditional football game, and Nicholas threw a bit of his money around, purchasing works of art and donating to the Nishi Honganji temple to help the poor. But what would remain pleasurably in Nicholas’s mind was their visit to the teahouses of Gion. As he would later write in his personal diary, “Hundreds of geishas filled Gion’s narrow streets. The teahouses’ residents are brocade dolls in kimonos woven with gold thread. Japanese erotica is more refined and subtle than the crude proffers of love on European streets… The tea ceremony ends… All that follows remains a secret.”

“Some members of the Japanese government were afraid that the Russians would rob them of the emperor, but Meiji insisted [going] on his own, saying: 'Russians are not barbarians, and they are not capable of such an act.'"

On May 11, seated in new jinrikishas sent down by Emperor Meiji, the duo — also accompanied by Prince Arisugawa Takehito — headed out for a day near Lake Biwa in Otsu, Shiga Prefecture. It was a relaxing day filled with scenic views, shopping (George picked up a bamboo cane) and good conversation. However, as the lengthy line of jinrikishas made its way out of Otsu, one of the policemen lining the narrow road had been harboring a boiling animosity toward the young and wealthy Russian royal. Even worse, he’d been assigned to protect Nicholas from anyone hostile — a duty he wanted no part of.

According to the July 1891 newspaper eyewitness account, Sanzo “drew his sword, and struck at the Prince’s neck. His Royal Highness — who was riding at the head of a long line of jinrikishas, with two coolies drawing him — jumped back as [Sando] cut at him, and the force of the blow was broken by his cap. However, he was cut on the head, and it is said that a small piece of the skull was chipped off.” Prince George, seeing the attack from afar, jumped out of his jinrikisha and ran after Sando, striking him with his bamboo cane. It did not bring him down, but fortunately two rickshaw drivers (Mukaihata Jizaburo and Kitagaichi Ichitaro, according to "Smart Histories" writer Tanel Vahisalu) abandoned their strollers and sprinted toward Sando, one of them tackling the officer and the other disarming him. Their quick and brave actions would end up being handsomely rewarded — the Japanese government eventually agreeing to pay them a lifelong honorarium of 36 dollars a year, while Nicholas (who was arguably the third wealthiest man in the history of the world, behind J.D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie) and his father gave them an award equivalent to $2,500, an incredible amount back then. Later, when Jizaburo and Ichitaro were given the cash amounts on Nicholas’s ship, the prince “told them to stop pulling jinrikishas, and settle down to something better.”

The attack, which occurred in “only a few seconds,” rippled across the two competing nations. Nicholas, according to Mescheryakov, “suffered all his life from headaches,” and had been traumatized enough to ask, every May 11, that the Russian public pray for his well-being. The “9-centimeter wound,” as Vahisalu reports, would be a lifelong reminder of how close to death he’d been.

As for Sando, two weeks after his attack, he was tried and sentenced to life imprisonment in Hokkaido. An odd irony exists about the sword he used, however. The proud nationalist must have used a police-issued sword, all of which had been forged overseas. If he’d used a sharpened, Japan-made katana, Nicholas would have been killed upon first strike. Several months into his life sentence, Sando died of pneumonia while in his jail cell, although others say he starved himself into a sickness.

Japan, and Emperor Meiji, stood embarrassed and angered by the attack. Meiji, to his credit, attempted to smooth over the feelings of the future Russian heir by traveling to the Azov, where Nicholas stayed, nursing his wound. As Mescheryakov describes, roughly translated from the Russian:

“Some members of the Japanese government were afraid that the Russians would rob them of the emperor, but Meiji insisted on his own, saying: ‘Russians are not barbarians, and they are not capable of such an act.’ During lunch, Meiji laughed a lot, [and] the emperor and the crown prince treated each other with cigarettes. Unlike the inveterate smoker Nikolai [was], Meiji did not smoke, but it was a special cigarette, a ‘cigarette of the world.’ Consoling Meiji, Nicholas said that wounds were minor, and craz[ies] were everywhere.”

In his personal diary, as reported by Nicholas II biographer Edvard Radzinsky, Nicholas gave most of the credit for saving him to Prince George, or “Georgie… my savior,” and his bamboo cane. Nicholas also admitted he carried no ill will: “[I] am not so very angry at the good Japanese for the repulsive act of one fanatic. As before, their model order and cleanliness is a pleasure, and I must confess I keep on watching… whom I see on the street from afar.” One moment continued to bother him, though, and it stemmed from the passivity of the surrounding Japanese bystanders, who’d only just before been happy to see him. “What I couldn’t understand was how Georgie, that fanatic, and I had ended up alone, in the middle of the street, why no one from the crowd rushed to my aid.”

The “Otsu incident” is sometimes credited as an event that raised tensions to a war-like level between the two countries, but thanks in large part to Emperor Meiji’s in-person visit, as well as a few “private” moments, it appears that Nicholas did not leave Japan with any kind of deep-rooted hostility, nor did many of his close associates believe he longed for war. On Jan 26, 1904, a little less than 13 years after Sando’s attack, Nicholas wrote in his personal diary: “… received a telegram… with the news that… Japanese torpedo boats had carried out an attack against the Tsesarevich, Pallada, etc, which were at anchor, and put holes in them. Is this undeclared war? Then may God help us!... ” Shortly thereafter, the Russo-Japanese War began, and Korea, Manchuria, and even a portion of Sakhalin Island soon were brought under Japanese control.

As for the rest of Nicholas’s life, a far grizzlier fate awaited than being sword-struck by a Japanese madman. On July 17, 1918, Bolshevik assassins gathered together the entire Romanov family (Nicholas, his wife and their five children) and brought them into a basement. A massacre ensued and within an hour, the 300-year Romanov family reign was over, their bodies burnt with acid. Nicholas was 50 years old.

Other stories in the Japan Yesterday series:

-- John Hersey visits the ruins of Hiroshima in 1946

-- Ralph Ellison makes himself visible in 1950s Japan

-- Audrey Hepburn Casts a Spell Over Post-War Japan

-- Bertrand Russell’s blinding Japanese resurrection

-- Birth control advocate Margaret Sanger brings 'dangerous thoughts' to Japan in 1922

-- Helen Keller brings hope and light to Japan

-- American President Ulysses S Grant talks peace in Meiji-Era Japan

-- Mrs and Mr Marilyn Monroe honeymoon in Japan

-- When Albert Einstein formulated his Japanese cultural equation

-- Charlie Chaplin tramps his way past a Japanese coup d’état

-- The Sultan of Swat Babe Ruth Visits Japan

Patrick Parr is the author of “The Seminarian: Martin Luther King Jr. Comes of Age.” His work has appeared in The Atlantic, Politico and The Boston Globe, among others.

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

11 Comments

Login to comment

Anonymous

Well said, Nick.

Nessie

Left quite a czscar

Kenji Fujimori

*as one eyewitness wrote in an 1891 letter to the British newspaper The Observer, “it was rumored that the objects of his visit were sinister and unfriendly — that [Nicholas] really came to spy out the weak points of the country.”

Interesting considering the British brought the opium epidemic to China and Asia, theyre colonial ways did more damage to Asia and Africa then Russia.

Kenji Fujimori

*Bolshevik assassins gathered together the entire Romanov family (Nicholas, his wife and their five children)

However this part is true, Bolsheviks are very evil, you should learn more about the damage they brought onto the world.

Kenji Fujimori

Patrick Parr, great article the way. Interestingly enough Biasedpedia deletes how the Bolsheviks murdered him and his family: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_II_of_Russia

Great writing and keep up the great content!

1glenn

Very interesting story. The unfair treaties brought shame to the countries which imposed them.

lostrune2

Hmmmmm...........

Hiro

So the sword was foreign-made and a Japanese one would have able to kill him? Oh, the irony.