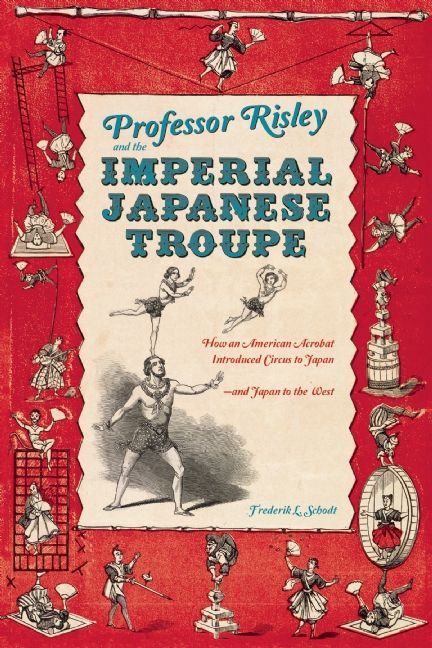

Having introduced a Western-style circus to Yokohama, world-famous American acrobat and impresario “Professor” Risley brought his “Imperial Japanese Troupe” to America and Europe in 1867.

These visits from Japanese performers helped trigger the West’s first craze for Japanese popular culture. Frederik L Schodt’s book is an exploration of a unique cultural connection with ramifications today: as we were seeing Japan for the first time, Japan was seeing us. Japan issued its very first passport to a member of Risley’s troupe in 1866, and a world-wide fever for all things Japanese was born.

In "Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe," Schodt presents an astounding collection of 19th century primary source material. News articles, letters, playbills, photographs and sketches capture this extraordinary moment of historic cross-cultural exchange between Japanese performers and Western audiences.

Schodt is the author of "The Astro Boy Essays," "Dreamland Japan" "Native American in the Land of the Shogun" and the editor-translator of "The Four Immigrants Manga." He often served as Osamu Tezuka’s English interpreter. In 2009 he received the The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette for his contribution to the introduction and promotion of Japanese contemporary popular culture.

What sparked your fascination with this character “Professor” Risley? It seems rather removed from your previous books on Astro Boy and Japanese manga.

Schodt: It’s true that I’m best known for my work on manga, but I’ve written many books on other subjects, too. I’ve written on U.S.-Japan relations, on Japanese technology, and on a Native American who visited Japan in 1848. I have a long-term interest in cross-cultural pioneers.

Several years ago, when in Japan, I saw references to Professor Risley and his Imperial Japanese Troupe. I was intrigued because — despite having written about Japan for decades — I had never heard of this colorful character, and I was not even aware of the popularity of Japanese performers in the West in the late 19th century. I love eccentric characters, and I love lost histories. I had an immense amount of fun writing this book.

Did Risley always intend to have a Japanese troupe of circus performers, or was his career path rather accidental?

Schodt: Since Risley left few written records, it’s hard to say with certainty what he thought, but there is no indication, at least until 1864, that he considered taking a troupe of Japanese performers to the West. I think his bold move was a function of having taken a Western circus to Yokohama, where his performers deserted him and he became stuck, and needing to come up with a new idea to make money. While famous for being an acrobat, and later an impresario, Risley was also an extraordinary entrepreneur.

Who were some of the stars of the Imperial Japanese troupe? How were they received in the United States?

Schodt: The biggest star, by far, of the Imperial Japanese Troupe, was a little boy known as “All Right.” His real name was Hamaikari Umekichi. In San Francisco, he quickly became the favorite of audiences for the panache and poise he showed. Like the other Japanese performers in the troupe, in the beginning he did not know any English at all, but he very quickly learned to exclaim “All right” and sometimes “You bet!” after executing particularly dangerous stunts. The audiences loved this, and nicknamed him “All Right.”

While he is not well-known today, in 1867 almost all Americans knew All Right. People spoke of him in conversation, and used his name as a metaphor for agility. Merchants were quick to jump on the bandwagon, and later there appeared All Right cigar labels and even a derringer named after him. E Mack, a popular composer of the day, wrote a polka to commemorate him, titled the “All Right Polka,” and the sheet music survives. My wife is learning the tune on the piano, and it’s a catchy, upbeat piece.

On New Year’s Eve, 1866, Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe arrived in San Francisco, the first American city the troupe encountered. How long were they in the city, and was their visit a success?

Schodt: The Imperial Japanese Troupe was in San Francisco for almost exactly a month, and was a huge success there. This was remarkable from two standpoints. First, in 1866/67, San Franciscans were fairly jaded; they had already seen a great variety of entertainers from around the world, including China. Second, another, smaller Japanese group — the Tetsuwari faction — beat the Imperials to San Francisco by a few weeks, but in short order the Imperials in effect routed their rivals from the City. The Imperials’ success in San Francisco is a testament to the skill of both the individual performers and to that of Professor Risley, who used his vast experience in the entertainment world to stage them in a way that enhanced their appeal to local audiences.

Your research for this book took you into archives around the world. What were some of the most surprising places in which you found information about Risley, and what did you learn?

Schodt: I visited archives and libraries on four continents, and found something amazing in all of them. But some of the discoveries outside of libraries were also extraordinary. For example, I discovered that the Cirque Napoleon, where the Imperials performed in Paris in 1867, survives today in virtually the exact same state, renamed the Cirque d’Hiver, and still hosts circus acts. As someone who is used to the musty newspapers, microfilm, and card catalogs of 20th century libraries, I must say that the on-line newspaper databases researchers can access today are extraordinary. I thought I would never find anything about Risley in Indonesia, but I was amazed one day to discover that on-line archives in the Netherlands have copies of the 19th century Java Bode, a Batavia (Jakarta) newspaper. In the 1861 editions of the paper, there are advertisements for one of Risley’s circuses, prior to his visiting Japan, in French, English, and Dutch.

You argue that Risley’s Imperial Japanese Troupe tour fueled the West’s first craze for Japanese popular culture, and that this obsession differs from the more well-known Japonisme art movement. How so?

Schodt: Japonisme is a very fuzzy and tricky word, and even many famous dictionaries do not bother to include or define it. Japonisme is usually associated with the art movement that emerged in Paris in the 1860s and '70s, when Japanese woodblock prints influenced the Impressionists, among others. The term can also be interpreted as a broader late 19th century infatuation with a unique Japanese aesthetic. Risley’s Japanese acrobats were part of the Japonisme movement and they helped fuel it, but they occupied a completely different space within it.

Fans of the Japanese acrobats of course included the high-brow, high-culture fans of Japanese woodblock prints and crafts. But they also included the working and emerging middle classes of America and Europe. In a sense, the influence of Japanese performing troupes was much greater that of Japanese artists at the time, because their audience was so much broader, numbering in the hundreds of thousands and including both the literate and illiterate.

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

No Comment

Login to comment