Amid rapid societal change around the world, the modern sharing economy has found both successes and struggles.

Ride-sharing company Uber, for example, has faced challenges from the local taxi industries in New York, London, and Tokyo—yet the service continues to grow. Lyft, HomeAway, TaskRabbit, DogVacay, and WeWork are just five more of the hundreds of services spanning a range of needs that have found success in the United States.

Home-sharing service Airbnb, founded in the United States in 2008, has seen enormous growth globally—and Japan is leading the way. New Year’s travelers were especially good to the company at the end of 2016. Aside from Tokyo, Fukuoka saw some of the highest growth in New Year’s Eve Airbnb bookings worldwide.

But the home-sharing service has faced legal questions in Japan and, as growth continues, the need to address these concerns is apparent. Thus, the current laws are being revisited.

Abenomics, the economic policies of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, has both weakened the yen and relaxed visa requirements, resulting in a spike in tourist numbers. For this reason, there are concerns that new guidelines being introduced by the government could impose crippling restrictions on the 48,000 Airbnb listings in the country, lowering Japan’s capacity for tourism.

However, it is believed that the Japanese government is ultimately looking to promote minpaku (private rental accommodations) to tackle the influx of tourists with the approaching Rugby World Cup 2019 and the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. The government is aiming for 40 million annual inbound tourists by 2020.

COPING WITH DEMAND

Part of the Japanese government’s plans for regional revitalization has been strengthening the tourism industry. As stated on the government’s website, this includes improving the ease of travel and stay for tourists by forming destination management organizations, training tourism management specialists, promoting national park and culture properties, and deregulating private room rentals for lodging in Tokyo and Osaka.

According to Japanese Tourism Research and Consulting Co., inbound tourism is surging, having reached 20,112,950 visits in 2016. Although this growth has economic benefits, it has also created high demand for accommodations. This is part of the reason that home sharing, or minpaku, has flourished.

Osaka’s Chuo Ward was rated Airbnb’s top destination in 2015, and the city’s Konohana Ward came in fourth the following year. Overall, in 2016, more than 3 million Japan-bound tourists chose to stay in an Airbnb.

The company’s growth can be attributed to changing travel needs says Mayuko Kawano, PR manager at Airbnb. “Tourists increasingly want new, adventurous, and local experiences when they travel,” she explained. “For them, Airbnb is the antidote to modern, mass-produced tourism; and our community allows them to experience cities and neighborhoods as if they lived there.”

Kawano added, “Overwhelmingly, Airbnb listings in Japan aren’t in the traditional tourist districts.” This is in line with global trends, where 74 percent of Airbnb listings are located outside of traditional hotel areas.

Last November, Airbnb announced a new partnership with Kamaishi City in northern Japan to promote rural tourism and revitalize the area. The aim is to attract travelers to visit the city ahead of the Rugby World Cup 2019.

“Airbnb [properties] in different areas help to redistribute tourism spend to local communities,” Kawano said.

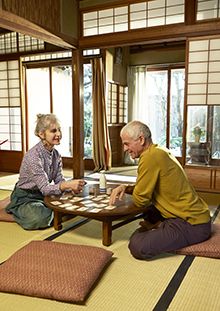

Highlighting the “economic lifeline” that the service is to many, Kawano pointed out that, in 2015, the typical Airbnb host in Japan earned ¥1,222,400. And with an aging population, it is promising that 14 percent of hosts are aged over 50 years; the fastest growing group is those over 60.

But with the financial and practical advantages come unanswered questions and obstacles, some of which are prominent in a society that values privacy.

“Trash, noise, and overuse of common facilities are some such problems,” said Eric Sedlak, counsel at law firm Jones Day in Tokyo. “These are likely to only be addressed if specific facilities prohibit the use of units as minpaku.”

Airbnb in Japan has sought to tackle this through an online tool that allows neighbors to send their complaints through to customer service, which will then contact the host.

LEGAL CONSIDERATIONS

In some areas of Japan, Airbnb has managed to overcome legal and operational barriers. After winning an exemption from Japan’s hotel law, Ota Ward became the first municipality to let residents rent out space to tourists in limited situations. Hosts must register with the local authorities and agree to inspections, and visitors have to stay at least one week.

Kawano believes such rules will “empower a new generation of micro-entrepreneurs across Japan, and increase consumer choice and help turn consumers into producers.”

There is no specific legislation in Japan that regulates home sharing. Some believe that minpaku such as Airbnb should fall under the Hotel Business Act of 1948, but other observers believe that amendments to the act have not kept up with the changing business environment. With the rise of home sharing and the increasing need for such services, the government has had to revisit the laws that govern hotels and inns to allow for these home-sharing services.

This applies to hotels and ryokans, but whether this is legally justified is unclear as minpaku—which provides a room in an individual’s home—is substantially different.

“A big difference is that the regulatory scheme is quite different, so that there is not a level playing field as among minpaku, hotels, and ryokans,” Sedlak noted. Hotels and ryokans are subject to stricter requirements such as safety, staffing, and training, and there are differences in how much they have invested in facilities, compliance, and personnel.

Yuri Suzuki, senior partner at law firm Atsumi & Sakai, explained why it is likely that Airbnb and other home-sharing services would fall under the Hotel Business Act (ryokan gyohou). “In this case, hotel business refers to a guest being charged an accommodation fee,” she said. This is unlike a leasing business, where the “tenant uses an apartment room as his or her home,” and so, the discussion that Airbnb might be considered illegal took root.

Thus, the law suggests that one must “obtain a license and be equipped with certain facilities,” Suzuki explained. It has been the case that many do not follow this and are therefore operating illegally.

However, Kojiro Fujii, partner at law firm Nishimura Asahi, highlighted, “Short-term rentals are not subject to the Hotel Business Act, but minpaku—in which the number of days stayed is typically less than a week—usually does not fall into this category.”

In addition, Suzuki explained, “recently it is getting easier to conduct minpaku service legally by compliance with relaxed regulations.” These new relaxed regulations comprise three categories. First, the government has had a National Strategic Special Economic Zone policy for the past three years under which certain cities can create their own short-term rental ordinances, provided guests stay for a minimum of 7–10 days. If requirements set by the city or prefecture are met, it is unnecessary to obtain a license under the Hotel Business Act.

Although the new legislation permits minpaku within National Strategic Special Zones, Fujii said: “This new system has not been utilized well because there remains a strict requirement on the number of days of stay, etc. And, in addition to that, the number of National Strategic Special Zones is limited.”

The order for the enforcement of the Hotel Business Act, Suzuki explained, was also amended in 2016. This was done to enable minpaku service providers to obtain a license under the act.

“For instance, while gross floor area of rooms of a certain category of the hotel businesses regulated by the Hotel Business Act must have been 33 square meters or more under the old enforcement order, in the case of minpaku service, where total number of guests is fewer than 10, floor area of rooms can be 3.3 square meters times the number of guests under the amended enforcement order,” Suzuki said.

Third, in June 2016, a panel set up by the Japan Tourism Agency and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare approved the use of paid accommodations in private homes in residential areas. The ministry is looking to submit the bill to the Diet by March, once talks have taken place with the ruling coalition. The minpaku law will allow businesses to provide accommodations for up to 180 days in residential areas, but will also allow municipalities to reject the establishment of these businesses.

But as Jones Day’s Sedlak pointed out, “even creating new rules to address minpaku use adds to the burden of the building and other residents, because building staff must enforce the rules.”

Globally, cities such as London, Paris, Amsterdam, Lisbon, and Milan have begun to embrace home sharing by making changes to Airbnb regulations.

Kawano said the company hopes the same will hold true in Tokyo, Osaka, and beyond: “We want to work together with policy makers in Japan on modern, simple rules for home-sharing that are right for Japan and easy for regular people to follow.”

CONCERNS

For those worried that Airbnb’s growth will negatively affect the hotel industry, Kawano emphasized that “occupancy rates of hotels in Japan have been growing steadily and have remained strong, despite the growth of Airbnb.”

In terms of the regulations, Nishimura Asahi’s Fujii cautioned that “the new act would hinder the development of minpaku if it imposes heavy and excessive burdens on hosts and online platformers such as Airbnb.” Strict administrative penalties and a duty to regularly oversee and report illegal hosts are two such examples.

He highlighted the importance of creating “a new act which is reasonable for hosts and online platforms.”

He added that, besides the law set by the government, voluntary rules and governance promoted by home-sharing services such as Airbnb “are equally important and may be even more suitable, in some sense, to realize the goal of promoting home sharing and minpaku.”

It is hoped that, overall, legislation will help enable the minpaku industry and extend Airbnb’s reach — not just in big cities but in rural parts of Japan. In turn, this should relieve the pressure on hotels to meet demand come 2019 and 2020.

Kawano echoed this thought: “Japan has a global reputation for innovation and hospitality, and has an opportunity to implement modern rules that benefit and enhance this hard-earned reputation.”

Custom Media publishes The Journal for the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan.

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

1 Comment

Login to comment

gogogo

Air Bnb is still operated 99% illegally in Japan due to stupid old boy laws. Uber has the same problem where its more expensive to use and takes 15 mins for a uber enabled regular taxi to arrive. You also pay for where they are now to you. .. There is no benefit to it, only clueless tourists use it.