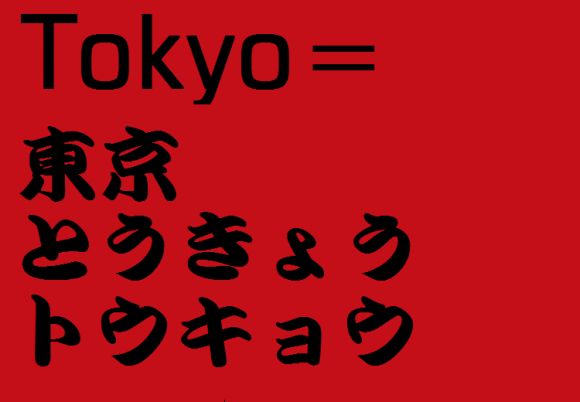

Yes, it’s true. Japanese has three completely separate sets of characters, called kanji, hiragana, and katakana, that are used in reading and writing. That first rendering of “Tokyo” is in kanji, with the hiragana version next, and the katakana one at the bottom.

The reason for this triple threat to language learners’ sanity isn’t that teachers of Japanese want to lessen their workload by convincing you to study Spanish instead. There’s actually a fairly logical, slightly lengthy explanation for using all three, so pour yourself a cup of green tea and let’s dive right in.

First, let’s take a look at kanji, which are complex characters, originally coming from Chinese, that represent a concept. For example, "kuruma," the Japanese word for “car,” is written in kanji as 車.

Hiragana, though, are much simpler in both form and function. They take fewer strokes to write than all but the simplest kanji, and instead of representing concepts, hiragana are used for writing phonetically. In other words, hiragana characters function like English letters, in that they don’t have any intrinsic meaning. They just represent sounds.

Because of this, any Japanese word that can be written in kanji can also be written in hiragana. "Kuruma," which we saw written in kanji as 車, can also be written in hiragana as くるま, with those three hiragana correlating to the sounds ku, ru, and ma.

So why do sentences have a mixture of kanji and hiragana? Because hiragana gets used for grammatical particles and modifiers. Remember, each kanji represents a concept. So when writing a verb, you use a kanji for the base concept, then hiragana to alter the pronunciation and add more meaning, such as the tense.

For instance, the verb "miru," meaning “see,” is written 見る, combining the kanji 見 (read mi) with the hiragana る (ru). If you wanted to change that to the past tense, "mita"/saw, you’d leave the kanji as is and replace the る with the hiragana た (ta) to get 見た/"mita," which means “saw.”

But wait, if anything that can be written in kanji can also be written in hiragana, why not use only hiragana? After all, while the complete set of 46 hiragana is bigger than the 26-letter English alphabet, it’s still way more manageable than the 2,000 or so regular-use kanji, the collected group that serves as the litmus test for full adult Japanese literacy.

Actually, there are three pretty solid arguments against writing exclusively in hiragana.

-

Because kanji were developed before hiragana, writing with kanji generally imparts a more educated and mature feeling. Sure, you could write "kuruma" as くるま and be understood, but it’ll look childish to Japanese readers, so adults are expected to go with 車.

- Still, if everyone in Japan did it, eventually the childish stigma of using only hiragana would fade away, just like if humanity collectively decides that, starting tomorrow, chocolate milk is a perfectly acceptable beverage to serve/request at formal business meetings.

But Japanese has a very limited number of sounds. Aside from famously having no L, very few consonants can be blended together, and every syllable has to end in a vowel or N. Because of this, the Japanese language is filled with words that are pronounced the same but have different meanings.

As a matter of fact, there are so many homonyms that without kanji, it can be confusing to tell which one is being written about. Sure you could write "koutai" in hiragana as こうたい, but "koutai" can mean “replacement,” “antibody,” or “retreat.” Because of that, if you want to get your point across, you’re much better off using kanji, 交代, 抗体, or 後退, to clarify which "koutai" you’re writing about.

- Japanese writing doesn’t put spaces, at all, between different words. This sounds like it would have the potential to turn every sentence into a confusing mass of congealed language bits, but written Japanese tends to fall into patterns where kanji and hiragana alternate, with the kanji forming base vocabulary and the hiragana giving them grammatical context.

For example, here’s "Watashi ha kuruma wo mita," or “I saw the car,” written with the customary mix of kanji and hiragana.

私は車を見た.

Right away, we can see the pattern of kanji-hiragana-kanji-hiragana-kanji-hiragana, which quickly tells us we have three basic ideas in the sentence.

- 私は: "Watashi" (I) and "ha" (the subject marker)

- 車を: "kuruma" (the car) and "wo" (the object marker)

- 見た: "mi–" (the verb “see”) and "-ta" (marking the verb as past tense)

Without the mix of kanji and hiragana, those breaks would be a lot harder to spot.

Suddenly, it’s a lot more difficult to tell where one idea stops and another starts, since it’s all one unbroken string of hiragana. Trying to read something written only in hiragana is kind of like tryingtoreadEnglishsentenceswrittenlikethis. The rhythm that comes from having a mix of kanji and hiragana, though, makes written Japanese an intelligible way of conveying ideas instead of a mad dash to the finish line.

Speaking of finish lines, we’ll be back again soon with this topic’s conclusion, in which we tackle the mysterious lone wolf outsider of Japanese writing: katakana, the third and final form of Japanese text.

Read more stories from RocketNews24. -- Foreigners in Japan vote for the best-looking katakana character -- The awesome artwork hiding in the Japanese word processor: sakura, dragons, and sake -- Struggling with Japanese? Let Tako lend you a hand…or five

© Japan Today Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

Take our user survey and make your voice heard.

59 Comments

Login to comment

Adam Shrimpton

Not sure if saying hiragana splits a sentence or ideas up is really a strong argument for using hiragana. For example, a bunch of nouns describing something / somewhere / someone don't have any hiragana 'fillers' to split it up. For example in a job title, you would write something like 阿部産業営業部長 (Abe Sangyo Eigyo Bucho - Sales Department Head, Abe Industries) and for an address you would write 東京都新宿区新宿3−1−12(3-1-12 Shinjuku, Shinjuku City, Tokyo). No hiragana 'fillers' there.

Also hiragana isn't used in Chinese - it's just kanji (hanzi) and no verb conjugations like in Japanese. So if you want to write 'I don't know' in Japanese you write (私は)知りません/知らない - (watashi ha) shirimasen / shiranai where the hiragana mixes it up. But in Chinese it's just 我不知道 (wǒ bù zhī dào) and just like Japanese, all words are written without spaces.

I think it's more to do with the fact that kanji have multiple readings in Japanese and verb endings / adjective endings etc. vary according to tense and the part of a sentence that it is. If they were just written with kanji, it would be very difficult to know just what reading they had, whereas Chinese doesn't have this problem (characters typically have only one or two readings) - imagine being able to read 知 as 'shiru', 'shirimasu', 'shiranai', 'shirimashita', 'shitta', 'shitte', 'shiri', 'chi' and others depending on conjunction and more..... In Chinese it's just 'zhī'.

So actually hiragana is a clever way of being able to write Japanese, allowing for Japanese grammar and the way words work, whilst retaining use of kanji to give a clear meaning of what words actually mean when written down. It's actually a very logical way of doing things - but hiragana is NOT a filler to break sentences up!!!

Fuben

Not that it will ever happen, but Japan would do well to simplify a little...

As far as I know, China go on pretty well using (basically) kanji only. Korea seems to be OK with hangul (equivalent of hiragana?) only. Vietnam, who used to belong to China, and used kanji, changed their whole writing system to roman letters and seem to have no problem communicating.

I think it would be nice if Japan got rid of katakana. In my opinion, it's just a useless addition, mostly serving o show something is not Japanese. Since hiragana and katakana also are exchangable, i see no point of katakana existing. Another minus point for katakana is that whenever something foreign is to be spelled, the katakana comes out, and more often than not, the results (in pronounciation and understanding of the difference between foreign languages) is horrendous. Katakana strips languages of many nuances that are important to get a feeling for a language. The French au lait in a café au lait is not the same as the Spanish olé, yet in katakana, they are both オレ.

Fox Sora Winters

@Fuben: but if you do away with Katakana, then au lait and olé would both be written as おれ, and the problem then still remains. There is a specific reason why Katakana is not only still used, but still needed, though that reason currently escapes me. I seem to recall reading that it was more than just for loan words, but even then it's handy to have a separate script for those, seeing as some loan words can sound similar to existing Japanese words.

Deborah Lansford

I'm surprised that the long history of hiragana and katakana seem as if they're treated like an afterthought. If something has been around since about the 5th century (and I wouldn't be surprised if people didn't start questioning it until Westerners arrived,) then it'll take a bit for noticable changes to occur to said thing.

bullfighter

Been there, done that. There was a major simplification and reduction in the number of characters used and taught in the postwar period.

But, if the language was changed to a phonetic scheme and people did not learn the historical system, only specialists would be able to read historical documents including laws.

This is a popular urban myth among gaijin. Katakana is widely used for purposes other than indicating foreign words and names. In my experience, university class lists usually give the pronunciation of Japanese names using katakana. Before computers could efficiently display kanji, all text was katakana. Telegrams were printed out in katakana. A few prewar magazines aimed at Japanese were entirely in katakana. Applications in Japan in Japanese for Japanese often require you to give the pronunciation of your name and your address in katakana.

Adam Shrimpton

Kind of. Hanja are still used sometimes for names of things and certainly for legal terms, but have fallen out of more general widespread usage since the 1980s.

Exactly.

It's still used a lot (not always) on till receipts in shops, supermarkets, restaurants and bars where they give an itemised list of purchases. So each word (even if it's a Japanese word) is written in katakana.

Scrote

Some of you give examples of situations where katakana is used, but in all those examples hiragana could just as well be used instead. Can anyone suggest a reason, other than convention, why katakana is necessary?

nath

Katakana can also be used for emphasizing words, or for breaking up a string of hiragana as well, to make it easier to see word breaks.

Theoretically you could drop katakana, but it would just make text more of a jumble. It's not a big deal to remember (even for school kids), and it gives an additional tool with which to transfer more meaning through text (by using it for emphasis on words, or identifying words as loan words etc).

Triring

Katakana is actually convenient in 8 bit computing since it is recognizable(readable) that is why it was used in the days of telegraphs. They placed spaces or breaks between words in those days too. Kanji cannot be represented in 8 bits which requires 16 and hiragana in 8 bits is messy to read.

nath

I think instead of just using romanji and being done with the extra katakana, they decided it was too foreign and had to make it Japanese. It created allot of headaches. You see Japanese do this with just about anything foreign. They not only change the original romanji word to katakana, the shorten and change it as well, so it now becomes Japanese, whatever that means.

Mike L

It's their revenge for English having r and l.

nath

I think if Japan would of been introduced to the Western world before they were to China, they would of adopted the English or Spanish language. Its just they were too close to China, and so they adopted everything from them. They met the Westerners too late in the game. Now their stuck with them Chinese customs and their language, trying to make it all work in this century.

inkochi

There are actually four writing systems for Japanese. The non-alphabetical ones are dealt with adequately here. The fourth type is the 訓令式 kunrei shiki(so-called 'government' system). It is in tandem and competition with the ひょお準式 hyoojun shiki (so-called 'standard system' better known as the Hepburn System). These are the romaji (roman script) systems

The former is normally found in students' English textbooks showing how to write something in romaji (like my student's name, しょうた comes out as Syouta. This looks really odd to people who normally read things as it sounds in English. But really it is just as valid a way to write things in a Roman script as it is in Italian, French, Vietnamese, Turkish or German. The Hepburn system was produced by Dr Hepburn towards the end of the 19th century and he based his simply as he heard things and reproduced them as English sounds - eg. つ as tsu and not tu, し as shi and not si, etc., or my student's name is written as Shota (though pronounced like 'shorta)'. Historically what happened was that Dr Hepburn submitted his system about 8 times to the early Meiji government department that later became the modern Ministry of Education, Science, Sport and Technology who are actually the administrators and bosses of the Japanese language in Japan. They always palmed him off though. By about 1896 or so, just after they had started compulsory general education (including English), the Ministry realised that they needed some kind of standard roman script system. The only one commonly around was Hepburn's and it had already taken off on thins such as railway station signs and company names. ANd as you could predict, there was no way that they were going to let a gaijin decide how to write Nihongo in any writing system. So people in the ministry got some experts and borrowed a bit from Italian, a bit from English and a bit from German and made a kind of pan-European language-based Roman script for writing Japanese. This was submitted once, about a month before Hepburn's final submission, and was accepted at once. And it is still there.

SO, yeah, I prefer Hepburn system because it makes my life easier in my lessons and doesn't do my head in. However, if a guy from here called Shota decides to write his name as 'Syouta', that would be normal for him as he would not be writing as English rather as Japanese. That needs to respected I think, even if you cannot get your head around his thinking as to deciding to write in that way.

It is a problem though when people here don't know any better than to believe that Romaji = English. That does my head in but, as they say, syouganai.

cleo

Fall at the first hurdle. The three sets are not 'completely separate' at all; hiragana and katakana are both derived from kanji.

Hiragana were developed from kanji to make writing easier for women, back in the days when everyone knew women were too stupid to study the new-fangled, learned Chinese texts imported from the big boys across the water. Text written in hiragana used to be called 女手(onnade) or 'women's hand', and was considered rather uneducated and childish - effeminate. Ironically, it is the stuff written by women in hiragana - The Tale of Genji, The Pillow Book, etc. - that form the core of classical Japanese literature, while the men at the time were struggling to write 'eddicated' kanbun - Chinese text using only kanji, with little markers to show the Japanese word order/syntax. That never really worked.

The one thing that really annoys and exasperates me is when learners of English, on being told that 'we don't say it that way' or 'we don't use that expression', want to know Why? Same with this. There is no reason at all for Japan to discard katakana, or discard the whole writing system and use the alphabet instead. The writing system as it is, does what it says on the tin. It works. Use it and revel in its possibilities, intricacies and foibles, instead of complaining because it ain't English.

nath

@cleo

The part of about the sexist nature of hiragana I did not know, thanks for the share.

But the logic of having to learn 4 alphabets escapes me. So you learn kanji, hiragana and katakana (the latter to battle the onslaught of English), only to unlearn it all to learn the 4th alphabet at the expense of national treasure.

nath

Romaji (no 'n').

You're right, but this article is about characters used for writing, not writing systems. There are only three Japanese sets of characters (kanji, hiragana, and katakana), with romaji being a non-Japanese set of characters that are used by the Japanese.

Wc626

Katakana is useless and very irritating. It screws up the pronunciation very simple words and names.

Example: My name is Robert, but (when changed into katakana) its Roberto, Robert"o" ! Where'd the "O" come from?

Have you every heard a Japanese person say, "Mc Donald's"? (as in the world famous fast-food chain) They add so many unnecessary syllables and pronounce it entirely wrong. Its frustrating to the native English persons ear.

CH3CHO

ScroteMAY. 13, 2016 - 10:26AM JST

There used to be a lot more forms of kana other than hiragana and katakana. Those archaic kana are called hentai-kana. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hentaigana

Since kana is simplification of kanji and there are many ways to simplify and many kanji from which to simplify, there were numerous hentai-kana to each sound of Japanese. In the last years of the 19th century, Japanese government made a good deal of effort to reduce the number of kana all the way to ONLY two sets. I do not know if people will further reduce the number.

By the way, English also has two sets of letters, the capital and the small letters. Is there any movement to unify the two for simplification?

kibousha

Japanese written language history is interestingly messy, according to history I read, Japanese had a spoken language first before Kanji was imported. You can guess how messy that was, trying to incorporate writings from a totally different language into an established spoken language. I'm guessing today's written Japanese is the result of 1000 years of "incorporation".

Interestingly, Korea who used Kanji before, decided to just get rid of it and made their own writing systems.

nath

That's not katakana screwing up the language, it's a basic fact of humanity that we can only speak in the phonemes that we know, and without learning the phonemes of another language, we are unable to pronounce, or for that matter even recognize, the sounds of the other language. English speakers bastardize the らりるれろ sounds of Japanese when trying to say Japanese words as well. Same with the きょう in とうきょう - English speakers say To-Ki-Yo, instead of To-Kyo. Should English start using Hiragana to write Japanese words that contain these sounds? Would that somehow make things better? Nope, because even if English speakers learned what these phonetics represented, unless they focused on learning Japanese, they would not be able to pronounce them the same way Japanese people do.

You are complaining about the pronunciation of Robert becoming ロバート, but try getting a non-Japanese speaker to say the name きょうたろう (kyotaro), and tell me that it it doesn't gain extra sounds in English that didn't exist in Japanese. Where did those sounds come from?

CH3CHO

kiboushaMAY. 13, 2016 - 02:41PM JST

English is written in Latin alphabets, which exist to record a totally different language from English. Latin alphabets are derived from Phoenician alphabets which existed to record a totally different language from Latin.

Koreans got rid of kanji or hanja in 1980s. So it is only one generation ago. We have yet to see the full effects of the loss of Chinese characters to Korean language and society. It is said 70 % of Korean vocabulary is kanji/hanja words. No one knows if Koreans would have limited vocabulary due to the loss.

cleo

CH3CHO's mention of hentaigana is interesting. The different forms of hiragana come from the fact that different kanji were used as the base from which the kana were formed. Scholars reckon that the different choice of kanji indicated some difference in pronunciation that was obvious at the time but later became lost. Study of the manyogana (the style of hiragana used to write the Manyoshu, an ancient collection of poems) indicates that at some time (around the mid-7th century) the Japanese language had at least 8 distinctly different vowel sounds that have over the centuries merged into the 5 we have today. The hentaigana probably reflected in some part the difference in pronunciation that was lost long before the hentaigana were abolished.

The interesting difference here is the the Latin alphabet was in Britain before the English language was. The Romans moved out before the influx of the Germanic tribes that brought the Anglo-Saxon language (aka Old English) to the Sceptre'd Isle. Old English was in fact an inflected language, with a pretty free word order, not all that different from Latin. And the spoken language was still developing while the means to write it down was already there. So using the Latin alphabet to write Old English was nowhere near as big a jump as trying to write a highly-inflected language like Japanese using the imported writing system of a non-inflected language like Chinese.

Strangerland is also right; it isn't the katakana that 'messes up' people's names, it's the phonemic structure of Japanese that insists that every consonant bar N must be followed by a vowel sound. I assure you the gaijin insistence on putting unnecessary intonation where it isn't needed in Japanese names is just as annoying (if you're the kind of person who gets annoyed at people who have accents.)

tinawatanabe

It is not Katakana's fault.

One thing for sure is that they wouldn't be able to read any historical documents with Kanji and more easily be brainwashed false history by their government. It may be the intention of their dropping Kanji.

Fuben

Oh, and I completely forgot about on-yomi and kun-yomi...

Of all the reasons I read in defense of katakana, not one seems to suggest the same couldn't be done with hiragana. I think, as is common in Japan, that convention and "but we have always done it that way" trumps any real logic when it comes to writing languages in Japan. Having three different writing systems (or four if romaji is included) ought to be seen as idiotic from a learning perspective, but is not, because it's been done the same way for ages. Just because you can remember them, doesn't mean it's a good, or even effective, idea.

mukashiyokatta

Because the Japanese people have intelligence.

kaynide

I honestly never understood why Japanese kana could utilize a new symbol to denote soft or no vowel pronunciation.

We have カ(ka) which can become ガ (ga) with a simple " mark. We have き (Ki) which can become きゃ (Kya) with the addition of a smaller "ya". We can even stretch sounds by adding a dash mark, so why not a symbol that denotes a soft or abrupt sound. We also have a circular mark to exclusively denote "P" sounds...

So again, why not a symbol to denote "No pronounced vowel here", take サラダ (Salada, as in a vegetable salad).

Why not サラダx, where this x (or whatever symbol) means just to mouth the "d" sound but not add any "a"

We could go from "Ku-Ri-Su-Ma-Su" to "K'-Ri-S'-Ma-S".. it would improve pronunciation tremendously... and having exposed my veteran students to Google Translate it is sorely needed for voice recognition.

nath

Because you've got it backwards. Written characters are used to represent the spoken language, they do not dictate it. The Japanese language does not have the phonemes to express the sounds you are discussing, which is why the characters also do not exist. The Japanese do not see the character ダ as being a combination of a D and an A sound, they see it as a single phoneme. Think of it for us as splitting up the sound of a random letter in the English language into two parts - it's almost impossible to consider, as those are our phonemes. It's why English speakers have so much troubles properly pronouncing らりるれろ - the phoneme to make these sounds doesn't exist in the English language. We could write something like 'rlisona' to represent the word りそな, but that wouldn't help any English speakers pronounce the word.

Fuben

Yet another problem I have with the damn katakana is that Japanese over-simplify many words when they "translate" foreign words. Take, for example the English word "steam".

This is perfectly possible to write with katakana as スティーム (sutiimu), but, probably because of the mendokusai of using one extra symbol, is written as スチーム (suchiimu), thus actively mispronouncing a word that would be no problem pronouncing correctly with current writing system.

"Pizza" (ピッザ) need not be pronounced "piza" (ピザ) just because someone decided it was mendokusai using three symbols instead of two.

I find katakana to be a flawed system, still used because nobody has the guts to question it. It might benefit the lazy mind, "japanizing" everything, but the way the world looks today, I find it better to actually learn about it than pretend everything is easily localized.

TheGodfather

Wrong! When all is said and done, it is "watashi wa kuruma o mita"

It is actually the "WA" sound written as "HA" because it's a human language, and it makes no sense...

Get over it!!

Triring

cleo

There are some relics still left like ”ヰ” within ニッカウヰスキー and not a ィ.

TheGodfather

Here's an idea for all you gaijin struggling with the reasons for, and uses of, katakana. Think of it like UPPER CASE CHARACTERS. The sounds are the same, the words are the same but the letters are written differently.

But some aren't different, just bigger. Why? For any reason I want to because it's my language.

Using an UPPER CASE character can denote many things. There is a difference between 'China' the country, and 'china' that one uses to eat and drink from.

Suzuki-san: That's nice china. Where did you get it?

Mr. Smith: Err, China!!

kaynide

@stranger: you have a good point, not sure why the downvote.

Anyway, my point mainly is if they can turn "ka" plus "yo" into "kyo", why not another symbol to denote "ka" becoming just "k"? They essentially already do it with kyo.

It would not have to be 5 different ones for ka ke ki ko and ku, but rather just one..like the ~o set...which again they already do kinda do.

nath

More likely because I'm the poster than because of the content.

Because just 'k' does not exist in the Japanese phonemic structure.

kaynide

@Stranger: right, I would push to make it exist.

Languages evolve over time... English used to have a unique character for the Th sound called "thorn" I believe. I mean, we could certainly go into cultural reasons, but dispite the impressive number of characters the available phonics is rather limited in Japanese. In country, this is all good, but it simply causes trouble or frustration.

Alternatively, a more difficult change, but one I would push even harder, is to completely abandon romaji and katakana entirely. No reason why they shouldn't just learn the actual English words in proper spelling.

Good example here...a student watched the movie Lovely Bones...she kept asking why it was called Love Reborn since teh character died..or perhaps it was Rub Ribbon...?

nath

So you would also say that English speakers should get rid of the word Tokyo, and learn how to write 東京 and how to pronounce it To-kyo instead of To-ki-yo?

kaynide

Not the Kanji, no, because the English characters Kyo should be pronounced as in Japanese. I would absolutely agree that English speakers should be taught correct pronunciation.

Same deal with Tsunami. The only one I am not sure how to tackle is the Japanese r/l hybrid. Americans kind of get away with crappy rr sounds in Spanish, so it is probably a lost cause...

nath

Ok, then how about the name れいな? Whether it's written Reina or Leina, both pronunciations will be incorrect. So should English speakers learn hiragana to read and write this name, and will that in turn teach them how to pronounce it properly?

nath

My point is the cultural superiority that some people here are showing in the criticism of Japanese people speaking their own language, using their own writing system, when we do the exact same thing in English. It's hypocrisy, and frankly ignorance. Almost all languages have borrowed words from other languages, and pronounce them in the way their own language is used. Ever tried to say 'sake' to someone back home? If you pronounce it the Japanese way, you just look pretentious. That's because we don't say it that way in English, we pronounce it 'saki'. The problem came about because of the use of English lettering - 'sake' looks like the word sake in 'for the sake of...'. So English isn't sufficient to express the proper Japanese pronunciation. We would need Japanese characters for that. But it's ridiculous to expect that. Same as it's ridiculous to expect Japanese people to stop using katakana, and to suddenly pronounce words the same as the English pronunciation, when they are not English speakers.

nath

Given

It is not just Japan, I have travelled the Globe and your de-facto English exists very little outside the business and tourist Industry.

Just try to speak to a local in English and most likely he won't understand you unless they learn English as a 2nd language and use it often.

Back home we learn English from the age of 7 but most people forgot most of it.

Holiday trips to Spain, Greece, etc we needed to learn the local lingo as few shop-owners could understand or use English.

Nerakai

Why do some people think Japan has to alter their language system to pronounce English, or whatever other foreign languages, properly when they, Japanese, don't really feel the urgency of the issue when they're still in Japan?

For the sake of foreigners' convenience in learning Japanese?

English spoken countries also import quite a few foreign words and pronounce them as they wish. What if the original language speakers of the loanwords complain about that?

Designer

OK well that makes it very clear then! What on earth are grammatical particles and modifiers!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

kaynide

@Stranger: I can respect that, but it puts Japanese at a disadvantage when they are purposefully taught incorrect pronunciation. With English it's the same especially when it comes to country names (and some said names have even become accepted or at least understood in their home country eg. Turkey or Paris)

Specifically to the Japanese, they already incorporate a lot of English/other languages as it is, and in many cases are taught incorrect usage because "it's easy". (eg "Aircon" or "Remocon") Many mistakenly believe it will be understood outside of Japan which is a problem. A minor one, but a common problem in my job. (I teach a lot of individuals who travel abroad for business)

My main point is that people all languages, if at all possible, should be taught to at least attempt correct pronunciation of words if they are applicable. Not shoved down their throat, but at the very least be aware that their usage is incorrect outside, but accepted locally. (One that pops up is the use of "Renew" or "Reform" for shops instead of "Renovate" or "Remodel" or the food "Hamburg").

Short version: Learn good habits at the get go and it's much easier than having to "unlearn" bad habits later.

nath

They aren't purposefully taught the incorrect pronunciation, they are taught the Japanese pronunciation of these words. Words take on a different pronunciation when they are borrowed into other languages.

These are loan words. They are now words in the Japanese lexicon, that have a root from another language. Like バイト. It comes from German, but it sounds nothing like the German, and is a Japanese word.

Only for a couple of days when they realize that they pronunciation is different than what they knew. It's a pretty easy lesson to learn for those who need to learn it, and at that time they will learn that the pronunciation of the English word (if they are studying English). On the contrary to this being a disadvantage, it gives them an advantage, as they have a base of Japanese words of English origin, making it easier to remember the English words as they learn them.

It has nothing to do with good habits or bad. They are learning Japanese, not English.

Particles are elements that connect parts of a sentence together. They can denote a subject or object, and or mean things like 'etc' or 'and'. Modifiers take a kanji and modify it to give it tense, or change the meaning, or make it causative or passive or whatever.

TheGodfather

"Learn good habits at the get go"

English people are thoroughly disgusted at such Americanisms.

kaynide

@Stranger: I can respect that, but I think we are going to have to agree to disagree. When I see Japanese talento on TV spoiting some nonesense English they think they picked up and completely misunderstand the meaning, other Japanese watch, listen and emulate.

We are talking a short check of the jisho, or something they grabbed from a cafe somewhere. If the source got it right at the start, incorrect usage/misunderstandings/awkward Engrish could be eliminated to a degree.

The usage of the words Smart, Revenge or Gorgeous come to mind. or Japanse business slogans like Inspire the Next. (The next...what?)

I get how they came into the language, and I do get that there will be wonky loan words in every language..but it comes across as ignorance. There is a reason why Engrish is a thing and stereotypical Japanese/Asian pronunciation is mocked. If Japanese in general don't care...well thats fine and I rest my case.

CH3CHO

kaynideMAY. 15, 2016 - 01:57PM JST

Believe it or not, it goes both ways and stereotypical pronunciation of the Japanese language by English speakers is mocked on this side of the shore.

As Strangerland pointed out, change in writing system does not cure the accent.

cleo

No, it started way before any English was heard in Japan. Look at all the Chinese loan words, the Portuguese loan words... Japanese is a sponge of a language, it likes to soak up whatever it comes into contact with.

It does go both ways, but I rarely hear Japanese mock folk who cannot pronounce Japanese words correctly. And I have never heard a Japanese demand that furriers learn kanji, hiragana and katakana to prevent them mispronouncing basic words. 広島(Hiroshima) almost invariably becomes hero-sheema: 着物(kimono), ki-mow-know: カラオケ(karaoke), carry-okki (which is extra-weird, since it's a reverse-loan word).

Demands/attempts to get the Japanese to abandon/modify katakana to mollify forn sensibilities is likely to have less success that the attempt by the likes of George Bernard Shaw to 'rationalise' English spelling to reflect modern pronunciation. There's nowt wrong wi' katakana, nowt wrong wi' English spelling.

Black Sabbath

Kana is absolutely necessary. But I see no real need for having both hira and katakana.

katakana and english spelling are not analogous.

kaynide

@Wipeout: Bit late to respond, but the 100 years ago argument is also illogical as you put it. Today we have the internet and live stream, global scale communication. Sure, in the 1800s it didn't matter if you butchered your Chinese in England because nobody'd be the wiser.

Today, it takes seconds to check a new word, especially when it first enters the language. Just because there is a historical precedent does not mean it is correct.

In addition, mostly what I am talking about is not even old words that have established 100-year usage. I'm talking the "Somebody didn't ask their gaijin friend before they started spouting nonsense on TV to the masses", such as Smart = Thin or Cunning = Cheating.

..or of course the more infamous question we're all wondering "Why the heck is my bill so expensive when the menu clearly says 'Free Drink'!?"

kannotomoya

bc Japanese are wise.

Timothy Aris

Link to part 2, because it wasn't added to this article for some reason:

https://japantoday.com/category/features/why-does-japanese-writing-need-three-different-sets-of-characters-part-2

阿部正司

A kanji and katakana were the formal character in the past.

An official document was written by a kanji and katakana.

When history is followed, Katakana is the male character.

Hiragana was the female character.

Japan was also male dominance in the past, so the Katakana which is the male character was used for an official document.

It's said to be because a Buddhist priest invented it that Katakana consists of a straight line.

It seems to be because writing implements in the time were a board-like bamboo stick, and a curved line was difficult.

some1

Today I have learned hiragana (yes even double) and I already have my view on 3 writing systems :D

This article author is explaining that the biggest reason for using 3 writing systems is to distinguish where words (sentence parts) ends and another begins by giving an example (in part 2) "Watashi ha meido wo mita/I saw the maid" by saying that if it is written like this : 私はめいどを見た than that big cluster of hiragana in the middle could be confusing.

True, BUT hey, I must be genius or what, why not using spaces between sentence words? You all (even Japanese speakers) say spaces. Why not writing it?

So above sentence would be: 私 は めいど を 見た. And even all in hiragana would be: わたし は めいど を みて. Easy-peasy!

Removing kanji characters does not mean that the meaning would be lost. Because if two speakers can understand each other by speaking (and they speak by hiragana sounds) then they could understand that written hiragana of kanji characters too.

サトル イアン

FWIW, the Man'yōshū was compiled in the mid-8th century, not the mid-7th, and study of the man'yōgana as used in both the Man'yōshū and Shinsen Man'yōshū indicates rather that the change happened no later than the 9th century, not "over the centuries".

Gem

@some1 why don't English just get rid of capital letters and change their spelling to reflect how it is actually pronounced?

Don't worry, there are some media that already incorporate spaces into Japanese text, like in some videogames, so your genius is very much appreciated.

Yes, indeed, people can understand each other despite the homonyms because of the context, but writing gives you the opportunity to express what you actually mean.

For example, わかる can be written as

分かる, 解る, or 判る, which all mean in the broad sense "to understand/know" but vary slightly in deeper meaning.

It is hard to explain, but in simple terms, it gives the writing a more precise meaning to indicate what the writer is actually trying to say. You know how English literature can have different interpretations, right?

Another reason is for brevity. Sometimes the word takes too much space when written in kana that they resort to using the less used kanji, especially in printed media like magazines or on TV when the kana would take up too much screen space.

Once you learn Japanese more, you would realize that Kanji makes the text more readable. Pure kana just gives me a headache when reading long text like in Pokemon.

Like I said, it is hard to explain, but once you delve deeper into Japanese, you would learn to appreciate Kanji.

If the Japanese themselves are not protesting about it (including the smart people), I don't think you have the credibility to tell them what to do with it.

Gabriel

This is why I hate being born with a terrible memory. I don't think I'd ever be able to even try to learn the language. It's a miracle I learned my own language. But it is still interesting to read about none the less!